Click to Download the PDF

Download the Word Doc

President’s Message

Welcome to the December edition of the Georgina Historical Society newsletter. Thank you to our members who were able to attend the 2021 Annual Meeting of the GHS at De La Salle Hall on November 18, it certainly was good to good to see everyone once again.

I would like to once again thank outgoing Directors, Barb Munro and Jackie Diasio for their long time service on the board. Their hard work and contributions are greatly appreciated. Also, Sandra Dickinson and Bob Holden have completed their terms as Treasurer and Vice President but will remain on the Board as Directors. Thank you Sandra and Bob for all your hard work , enthusiasm and dedication to the GHS.’

I would like to introduce the 2022 GHS Board and thank them for volunteering their time to serve on the GHS Board:

Directors: Dee Lawrence, Sarah Harrison, Elizabeth McLean, Sandra Dickinson, Wayne Phillips, Bob Holden

Executive:

Treasurer; Sue Horton

Secretary; Gail Moore

Vice President; Paul Brady

Past President; Karen Wolfe

President; Tom Glover

The 2022 calendars, featuring buildings and structures in the Pioneer Village are now available for $15. A great Christmas present for family and friends, you had better get yours before they are all gone.

Wishing you all the best for the Christmas season and the New Year! Take Care! Stay safe!

Merry Christmas Captain Johnson! By Karen Wolfe

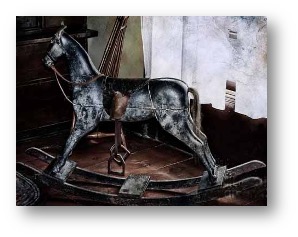

On December 25 1837, Pefferlaw founder Captain William Johnson was arrested for treason in his home as he sat down to enjoy his Christmas dinner with his family. 1837 had been a year of unrest in Upper Canada (currently Ontario/Canada West). Farmers and rural homesteaders had become increasingly dissatisfied with the Family Compact, a ruling regime that favoured patronage appointments to fill key political positions. Those loyal to the Family Compact were also loyal to the British crown. Many were faithful members of the Orange Order–an established protestant organization with conservative values and an allegiance to the British monarchy.

The faction of Upper Canada citizenry that were critics of the Family Compact were known as reformers and were led by William Lyon Mackenzie, an advocate for self-government and a campaigner who supported Canada as a republic. For years leading up to 1837, Mackenzie and his followers had urged the colonial government to listen to their grievances and had hoped for a peaceful change in ideology that would demonstrate a trend toward democratic reform. But that was not to be.

Captain William Johnson

It is no secret that Capt. Johnson’s sympathies supported the reformer’s agenda but he was a moderate reformer and drew the line at armed conflict. He was a local Commissioner and he wrote extensively in his diaries about his numerous communiqués to and from Mr. Mackenzie.

“March 25, 1836. Received letter from McIntosh, David Sprague and two from Mackenzie. Petition to House of Assembly.”

And it seems his allegiance in this direction attracted attention by some of the other local personalities who clearly supported the Family Compact. Before the close of 1836, Lieutenant-Governor Sir Francis Bond Head had received a report which discussed Capt. Johnson’s affiliation with Mackenzie. Here are two of his diary entries…

“May 5, 1936 – Received a letter from the Lieut. Governor thanking me for my explanation of the charge laid against me by the four informing Tory Commissioners, Arad Smalley, Frances Osborn, James O. Bouchier and Henry Stennett exculpating me from any blame.”

“October 21, 1936 – Received from the Lieut. Gov. the spy Arad Smalley’s report to his Excellency of my political delinquencies.”

On November 7, 1837, a month before the insurrection, Capt. Johnson’s makes a note in his diary that he sends a letter to Mackenzie and encloses $5 dollars “to assist him in paying his expenses for the Will and Libel”. Then on December 6, he makes another notation saying he heard that Toronto was taken and that Montgomery was shot. On the next day, December 7, 1837 (the day of the uprising) he writes this…

“December 7, 1837 – Messrs Bouchier, Jack and Howard came with an armed band of Tories to ask me to levy war against Reformers, which I promptly refused.”

His decision to take a side against men he had previously counted on as friends, played heavily on him.

“December 13, 1837 – Unhappy day for me severing friends with Turner and some of my former connections.” (Turner was his brother-in-law.)

Following the failed attempt at Montgomery’s Tavern, rebel forces fled far and wide. Many eluded capture by escaping to the United States when government forces began searching for anyone thought to be involved in the rebellion. Reports suggest that over 800 people were arrested for being Reform sympathisers and certainly Capt. Johnson’s refusal to “join the armed band of Tories” was not lost on those who felt that denouncement was an act of treason.

When Capt. Johnson’s 1837 Christmas dinner was interrupted, he always described the intrusion as an “indignant feeling” when he was carried before the Commissioners at Toronto for High Treason “by a banditti of vile Orangemen” with “no warrant except their pistols.” He believed the Orangemen were “seconded by a not less vile magistrate who encouraged them in their improper proceedings.”

On December 27, 1837 he wrote…

“Went to Toronto to answer the charge of High Treason” and he returned home on December 29, completely exonerated.”

Although the rebellion itself failed, it did bring attention to the issue of self-government and Capt. Johnson continued to champion the cause for responsible government and democratic reform. He lost friends over his reform attachment but he proudly hosted visits by Robert Baldwin, the first premier in Canada West to lead a responsible government in 1847.

On Christmas Day in 1847, ten years after he was arrested, Capt. Johnson wrote in his diary…

“By our exertions I am pleased beyond measure that we can now sit down to safety under a benign and responsible government. Fortunate constitutional existence.”

Early Christmas Traditions

The following has been modified and adapted from a blog by Gerry Burnie at: https://interestingcanadianhistory.wordpress.com/2014/12/19/pioneer-christmases/

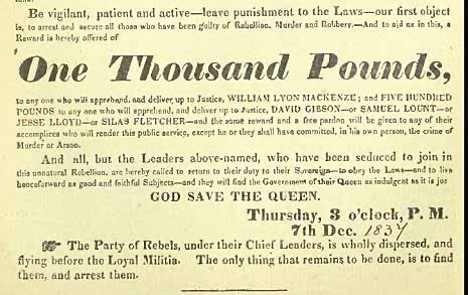

Stockings were hung on the mantle or bedposts. If the harvest had been plentiful and the children well behaved, the stockings were filled with presents.

A gingerbread man might have been included, but if so it would have been molded by hand. There were no such things as cookie cutters, wrapping paper, or cards.

Left – Hanging a stocking before Christmas

Often, an apple or a home-made sweet was dropped into the stocking. Maybe even a treasured item such as a jack knife or cornhusk doll would be included. Perhaps if someone in the family knew how to whittle or work with wood, a puzzle or figurine would be found.

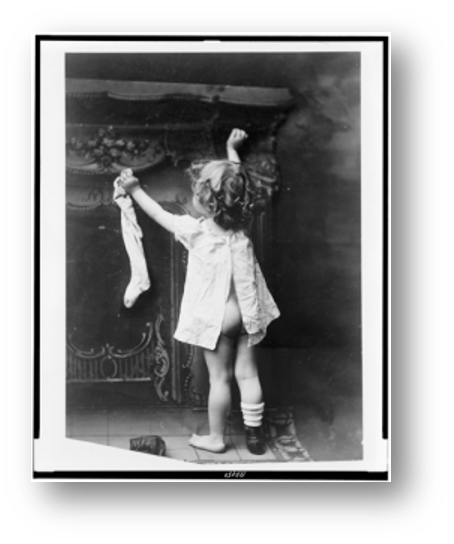

Right – Rocking horse from the mid-1800s

Wooden rocking horses were often made for small children. Such horses sometimes turn up today at antique sales. The carvers of these pieces would hand-rub the contours of the horse to a smooth finish and add a horse hair mane and tail. Then, the eyes and a saddle would be painted on. A bridle and reins of cloth, animal hide, or tiny chains might be included as well. These early rocking horses were magnificent specimens of early Canadian handcrafts. Other toys given to children were such treasures as a homemade sled or snowshoes. These brought many hours of winter fun.

Below is excerpted from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/christmas-in-canada; the following article explains why Christmas falls on December 25th.

Why is Christmas on the 25th of December?

Whatever the origins of the festival that is held on the 25th of December, it cannot be the celebration of the actual birth date of Jesus. That date is unknown. So while Christmas is the day on which the birth of Jesus is celebrated, the day chosen seems more related to the many festivals that mark the winter solstice, most of which in Roman or Celtic times predate the birth of Jesus. While it cannot be said that these festivals are the origin of Christmas, they have left their legacy not only in the time of year, but also in many of its symbols and traditions.

Winter solstice festivities of course celebrated renewal and the return of light, a perfect complement to the birth of Christ, which, according to the Christian faith, brought light into the world to dispel the darkness of sin and radiate the love of God. In the Northern Hemisphere, the solstice occurs everywhere at the same time between 20 and 23 December, based on the Gregorian calendar, but local time may be on 21 December in Western Canada and 22 December in Eastern Canada.

The Pagan Antecedents to Christmas

Solstice festivals, marking the low point of the sun, the shortest daylight of the year, the time from which days will lengthen and hopes for light and warmth will reappear, have been celebrated perhaps for millennia in northern climates, where winters are more severe.

One of these festivals, the Roman solar feast of Natalis Invicti, celebrated on 25 December, may have a strong claim as the origin of our late December date for Christmas. This solar cult reached its climax under Emperor Aurelian (270-275). Later Christians, eg, Chrysostom in the 4th century, made a connection of this festival with the birth of Jesus: “if they say that it is the birthday of the Sun, He is the Sun of Justice.”

Also in Roman times, Saturnus, the god of seed and sowing, was honored with a festival. The Saturnalia was officially celebrated on 17 December and, in Cicero’s time, lasted seven days, from 17 to 23 December. In the Roman calendar, the Saturnalia was designated a holy day, on which religious rites were performed. But it was also the most popular holiday of the Roman year, an occasion for visits to friends, for drinking, and for the presentation of gifts, particularly wax candles, perhaps to signify the return of light after the solstice. The Saturnalia continued to be celebrated down to the Christian era, when, by the middle of the fourth century AD, its festivities had become absorbed in the celebration of Christmas.

In North America, some First Nations also held winter ceremonies and festivals as a time for regeneration and introspection. Some, such as the Iroquoian groups, held week-long festivals at mid-winter, with the time determined by observing the moon and stars. It eventually came to be associated with the winter solstice. Typical practices, some of which continue to this day, were healing rituals, making tobacco offerings, prayer and ceremonial drumming and dancing.

Early Christian Dates for Christmas

Some of the earliest records for the celebration of the birth of Jesus come from Alexandria, Egypt. Several scholars, dating back to Clement of Alexandria (c. 200 AD), have attempted to determine the exact date of Jesus’ birth. The date has yet to be determined, but Clement notes that Epiphany and the Nativity were celebrated on 10 or 6 January, indicating that some sort of consensus was reached. The commemorations became popular in Egypt between 427 and 433. At the end of the fourth century, in Cyprus Epiphanius asserts that Jesus was born on January 6th and baptized on November 8th.

In Jerusalem in the fourth century the Birth and Baptism were still combined in a single event. There is a record of Cyril of Jerusalem (348-386) writing to Pope Julius I (337-352), declaring that his clergy cannot, on this single feast, make a double procession to Bethlehem and Jordan. He asks Julius to assign the true date of the nativity based on the census documents brought by Titus to Rome, and Julius assigns December 25th. But Julius died in 352, and by 385 Cyril still had not made the change.

Hence there were precedents when Pope Liberius I (reigned 353-356) preached a sermon at St. Peter’s, instituting the Nativity feast in December. By the end of the fourth century the feast was established, and every Western calendar assigned it to December 25th. The new date reached Constantinople by 379. In the Western church, Epiphany is usually celebrated as the time the Magi, or Wise Men, arrived to present gifts to the young Jesus (Matt. 2:1-12). Epiphany, also called Twelfth Day, is typically celebrated on January 6th, culminating the observance of Twelfth Night on January 5th. Since Eastern Orthodox traditions use a different religious calendar, they celebrate Christmas on January 7th and observe Epiphany, or Theophany, on January 19th.

The Second Council of Tours proclaimed, in 566 or 567, the sanctity of the “twelve days” from Christmas to Epiphany and the duty of fasting on particular days of Advent (period beginning on the Sunday nearest the feast of St. Andrew, on 30 November, and including four Sundays) to prepare for the celebration of Jesus’ birth. Fasting was forbidden on Christmas Day and eventually popular merry-making so overwhelmed the religious aspects that the “Laws of King Cnut,” c. 1110, ordered a fast from Christmas to Epiphany.

Christmas Cards and other Christmas Traditions

In 1843 Henry Cole commissioned an artist to design a card for Christmas. The illustration showed a group of people around a dinner table and a Christmas message. At one shilling each, these were pricey for ordinary Victorians and so were not immediately accessible. However the sentiment caught on and many children – Queen Victoria’s included – were encouraged to make their own Christmas cards. In this age of industrialisation colour printing technology quickly became more advanced, causing the price of card production to drop significantly.

Together with the introduction of the halfpenny postage rate, the Christmas card industry took off. By the 1880s the sending of cards had become hugely popular, creating a lucrative industry that produced 11.5 million cards in 1880 alone. The commercialisation of Christmas was well on its way.

Another commercial Christmas industry was born by Victorians in 1848 when a British confectioner, Tom Smith, invented a bold new way to sell sweets. Inspired by a trip to Paris where he saw bon bons – sugared almonds wrapped in twists of paper – he came up with the idea of the Christmas cracker: a simple package filled with sweets that snapped when pulled apart. The sweets were replaced by small gifts and paper hats in the late Victorian period, and remain in this form as an essential part of a modern Christmas.

The Toronto Santa Claus Parade

The Toronto Santa Claus Parade, also branded as The Original Santa Claus Parade, is a Santa Claus parade held annually on the third Sunday of November in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. More than a half million people attend the parade every year.

First held in 1905, it is one of the largest parade productions in North America, the oldest Santa Claus parade in the world, and one of the world’s oldest annual parades. Its current route is almost 5.6 kilometres (3.5 mi) long, running from Christie Pits along Bloor Street West, south on Avenue Road/Queen’s Park Crescent/University Avenue to Front Street West, and east along Front to St. Lawrence Market.

The idea for the parade originated from an earlier promotion by the Eaton’s chain of department stores, on 2 December 1904, when Santa walked from Union Station to the downtown Toronto Eaton store on Queen Street. The first official Toronto Santa Claus Parade was first held on December 2, 1905 with a single float. Sponsored by Eaton’s, Santa was collected at Union Station, and delivered to the downtown Toronto Eaton’s store.

From 1910 to 1912, the parade began its journey in Newmarket on a Friday afternoon, stopping overnight in York Mills and then continuing south along Yonge Street to Eaton’s downtown Toronto location on Saturday afternoon.

For the 1913 parade, Eaton’s brought in reindeer from Labrador to pull Santa’s sleigh. Until 1915, the parade was followed by Santa holding court at Massey Hall where he would meet with up to 5,000 children. Since then, the parade has grown in size each year and today attracts large crowds with thousands of children waiting with bated breath for Santa’s arrival.

From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toronto_Santa_Claus_Parade

Where in Georgina?

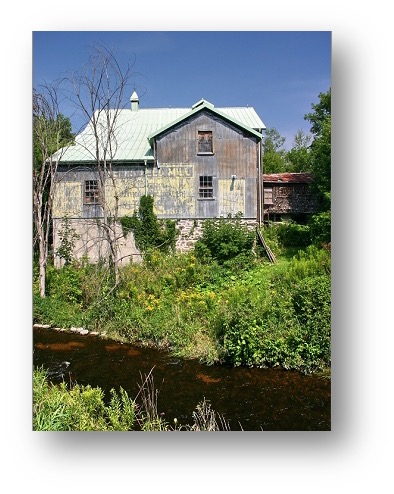

Left is an earlier location correctly identified by Cora Raine as Hadden Road. Last month’s mystery location was identified at the AGM as the bridge at Paradise Beach. So we now have a new location.

Where in Georgina is this new mystery location?

Get Your New 2022 GHS Calendars!

The calendar will sell for $15. Proceeds from the sale of the calendar will be used to complete the refurbishing of the caboose at the Village. To purchase your calendar contact a GHS Board Member or contact Tom Glover at:

905-722-0180 or 905-830-2575

btglover@rogers.com

News

On November 18 our Annual General meeting was held at De La Salle hall. A new Board of Directors and officers was elected and there was a presentation of the Heritage Award from the Town of Georgina to Karen Wolfe, our Past-President, for her passionate work in preserving our past. This was followed by a slide presentation by President Tom Glover documenting the wonderful progress by the Town of Georgina improving the Pioneer Village and some of our concerns regarding the preservation of local history.

Left – Kim, Sue, and Sandra preparing refreshments for the AGM.

Right – Your new GHS Board of Directors and Executive…

From left to right – Tom Glover, President; Bob Holden, Director; Karen Wolfe, Past President; Wayne Phillips, Director; Paul Brady, Vice-President; Sue Horton, Treasurer; Elizabeth McLean, Director; Sandra Dickinson, Director; Dee Lawrence, Director; Gail Moore, Secretary.

Absent: Sarah Harrison, Director

Presentation of the Heritage Award to Karen Wolfe

From left to right: Dee Lawrence, Heritage Committee; Mayor Margaret Quirk, Town of Georgia; Terry Russell, Chairman of the Heritage Committee; Karen Wolfe, Heritage Award recipient.

Events

First Saturday in December (December 4) – Sutton Santa Claus Parade

Month of December – “Festival of Lights” along the Parkway between the Village and the ROC

Monday, January 3rd – Board meeting at the Noble House