Click to Download the PDF

Download the Word Doc

President’s Message

There are only 5 calendars left. If you know of anyone who wants one, please contact me or any of your Board members, while there are a few remaining. To date our little fundraiser has netted over $1200 for our caboose restoration. Thank you for your support in this endeavour.

It looks like it will be a while yet before we are able to resume our regular meetings. Since we usually have our “Bring & Brag” for our January meeting, please send a picture of an article you have and a little description for us to include in an upcoming newsletter.

Looking forward to seeing everyone once again in 2021!!

Take Care! Stay safe!

Tom Glover,

GHS President

Bring and Brag 2021

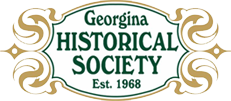

Pocket Watches – by Tom Glover

You may remember your father or grandfather reaching into his vest or overall pocket and pulling out his pocket watch to check the time. I remember Dad’s pocket watch attached to his overalls, not by a gold chain but by a leather boot lace. You did not want to lose such an important item.

Recently my elderly (101 year old) mother gave me a precious object. My grandfather Russell Glover’s pocket watch had sat in a drawer in a cloth pouch since his death in 1944. My father, although very pleased to have his father’s watch could never bring himself to use it.

It remained untouched all those years. As I held the watch in my hand, I could not believe how heavy it was and then I could not resist winding it. The watch started ticking, so I set the time and waited. After 76 years of lying in a drawer the watch not only ran but kept perfect time. What a tribute to the workmanship of a previous generation!

I also have my great grandfather, Joseph Glover’s pocket watch dating back to the 1850s. The case is not silver or gold but tortoise shell.

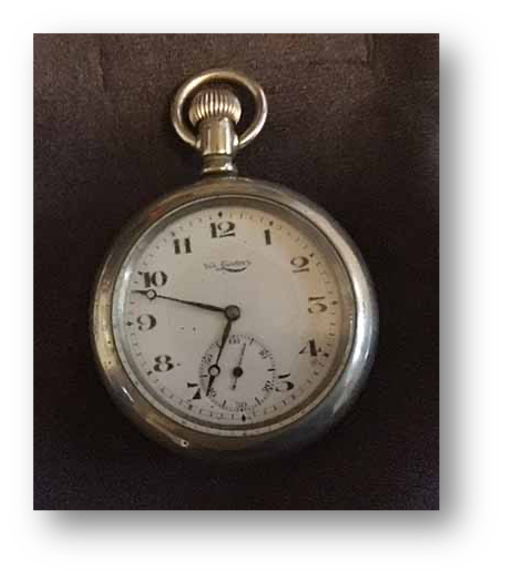

Unfortunately it is wound with a key and the key is missing. This watch dates back to the late 1850s. Tucked in the back of the watch are paper tickets from Geo. Palmer, the watchmaker / jeweller in Bradford. With my grandfather’s name or initials and date on one side and the jewellers label on the other they verify the transactions. I have been able to decipher dates back to 1857.

Apparently it was important to have the watch cleaned and checked out once a year! The writing on the paper was probably done up on a day’s excursion from Ravenshoe to Bradford to get to the watchmaker in the mid-1800s.

Above – the name of the watchmaker in Bradford

I would love to know the story behind my great grandfather’s watch. Was it a gift to an eldest son on his 21st birthday? …an inheritance or a young man’s first important purchase? Always mysteries to solve

A Progress Report: Our Caboose

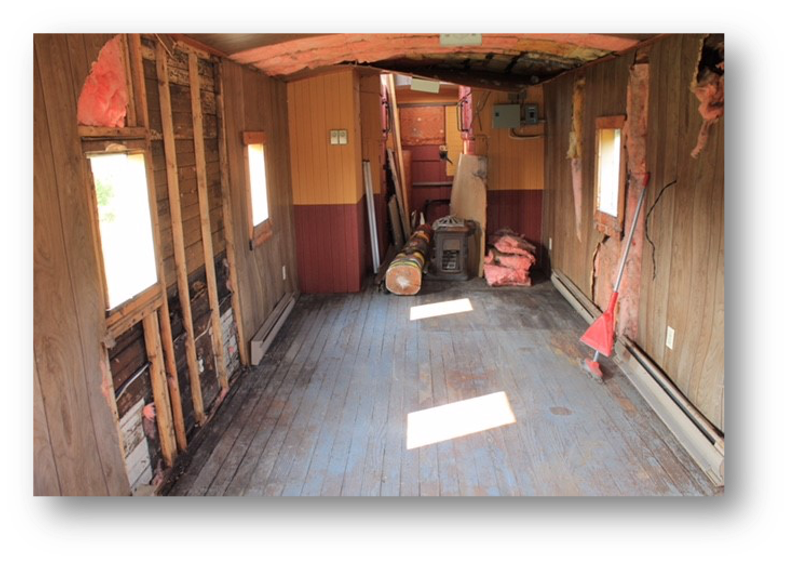

As you know, we reported in a previous issue that the roof of our caboose had been redone. Next page shows before and after images of the progress on the interior; recently insulation and new panelling have been installed making the interior weatherproof and ready for further restoration.

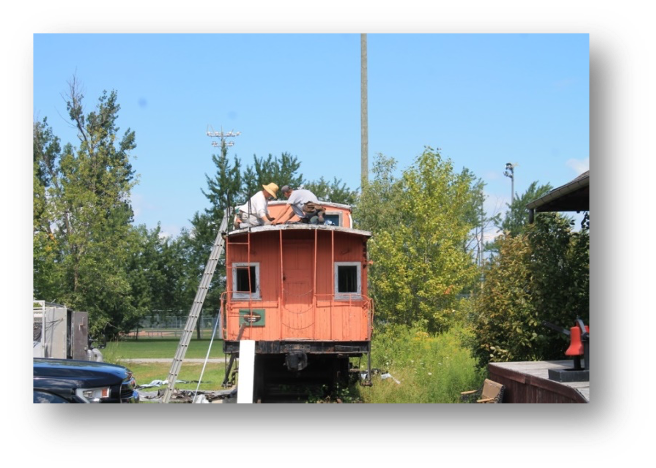

Right shows roofers hard at work on the caboose roof. Thank you Paul and Wayne for your many volunteer hours.

Before

After

All about Cabooses, Vans, and Crummies

Condensed and edited from trainweb.org by Bob Holden

Cabooses have mostly disappeared on our railways and those that remain must mostly be visited in a museum. In Canada, railway personnel referred them as vans, though south of the border caboose and crummie were far more common. A look inside a caboose has always been restricted to those having a reason for being there. Few outsiders knew exactly what was inside a caboose, or what went on in there, other than it being a place for the crew to ride. In fact, it was an office and home-away-from home as well as a lookout for observing the train and the right-of-way while in transit. It was also used for crew transportation in larger terminals, and as crew headquarters for maintenance of way work and emergencies or accidents.

A conductor and two brakemen ate and slept in their caboose, which was always assigned to them for their exclusive use. More recently, cabooses were pooled for mainline trains and only assigned to local and branchline train crews who kept their own van. Pooled cabooses stayed with a train to final destination and the crew slept in a bunkhouse like the engine crews had always done. Two brakemen (one riding the engine and one on the van for flagging and switching) were reduced to one brakeman, and in the case of many cabooseless trains just a conductor. These “conductor only” trains were once limited to the amount of enroute switching they were required to do. This restriction was soon eliminated. Cabooses are for the most part now are used only on trains that have to make frequent backup moves. These are called a “platform”, a safe place for a crew member to ride as access to the interior has been eliminated. This required the return of the emergency airbrake valve back to the platform. Brakemen are all called trainmen now but years ago trainman referred to a man working in passenger service, just as switchman has been replaced by yardman although both terms were used interchangeably. The CPR stated that it cost $100,000 per year to operate and maintain each caboose, so there were great savings to be had. By the end of the 90’s cabooses had all but disappeared and had been replaced by a FRED or flashing rear-end device.

All vans were equipped with a kitchen and coal stove where meals were cooked and eaten at the “foreign” or away-from-home terminal, or even enroute on long days and nights with no end unlike today’s 10-12 hour maximum. Coleman camp stoves were once used for cooking after oil heaters replaced coal stoves. What they ate in their cabooses depended upon the cooking talents or lack thereof on the part of the crew. The inside of cabooses reflected the conductor’s personal habits and the degree of cleanliness varied with some men being noted for spotless vans while others were much less so giving rise to an old term for vans as “crummies”. It was the junior brakeman’s “duties” to stock up the van with coal for the stove and to wash the floor to the satisfaction of his conductor. There are many stories about young “green” brakies and one that fits here is about the conductor who finds himself with two spare men he doesn’t recognize. (In fact, a conductor was not required to take two spare men if they were too green) He demands to know, who is the senior man; and when one pipes up, he tells him to couple all the hose between the caboose and the locomotive and then tell the engineer all right. He then tells the junior man to get the mop and pail and get busy washing the floor. Of course in any yard having carmen on duty it was they who did up the hose bags, but that spoils the joke. Upon reaching the locomotive the green brakie tells the engineer “all right” (can you see it coming?) Whereupon the hogger growls, “all right, what?”

“Why turn on the water, they’re going to scrub out the caboose.”

The cupola is a lookout point where the crew rode to watch for trouble with the train, an important safety feature. Things they would watch for included smoke or fire from a hot box (wheel journal), shifted loads, dragging equipment, any evidence or signs of freshly damaged ties etc. as seen from a rearward look. There was also an air brake gauge and emergency brake valve in the caboose..

What was generally not known by most people including railroaders not directly concerned with trains was just how much equipment was carried in the caboose. Some of this equipment was to allow the crew to make emergency repairs to their train. Back in steam engine days trains often consisted of 36′ and 40′ freight cars having friction bearings with waste packing. This type of journal resulted in a high number of hot boxes (overheated bearings) and was one of the reasons so many car knockers were needed to check every car at every terminal. Carmen were called “car knockers” or “car toads” because they used to carry a hammer to hit the wheel with a good wheel giving off a true ring while a defective one made a dull sound or thud. This was important especially since cast iron wheels were subject to more defects and failures than more modern steel wheels. They were referred to as toads, since they were always hopping about around and underneath cars looking for troubles. Hot boxes developed mostly from lack of proper lubrication due to either no oil or because of a waste grab whereby the packing got jammed up and could not distribute oil properly to the axle. Often caused by high impacts from too fast couplings during switching whereby the car would jump up disturbing the packing, car inspectors carried a packing iron and a oil can with them to lift up the journal lid using a hook on the iron to look at the oil level and tamp the packing back in place if necessary. At night they also had to carry a light to see what they were doing. Often this was a carbide lamp that gave off a very powerful and bright pure white light. The lamps were never turned off during a shift so they would be set down outside (because of fumes given off ) with the reflector facing the wall. At times, the oil and waste would catch fire and this was one of the things the crew watched for. As long as the flames could be seen they would try to make the next siding, but once it burned out there was nothing left to lubricate anything with and an immediate stop was necessary to prevent a burnt off journal axle from derailing the train. Senior railroaders and pensioners remember those days and they shake their heads at the many things they see today, no doubt old timers would turn over in their graves if they knew what was going on now.

Lubricator pads replaced loose waste and eliminated a large percentage of hot boxes since the material stayed in place better. Costing a tiny fraction of roller bearings, they provided almost as good a result. Roller bearings were expensive and only used on passenger cars, locomotives and heavy capacity freight cars. Gradually, the advantages of roller bearings outweighed the negative factors. Hot boxes were dealt with by the train crew by adding a special cooling compound to nurse it along and or by repacking the journal, or in an extreme case such by having to stop right on the main line and re-brassing it. A heavy jack was brought out of the van and lugged into place to jack up the offending journal and replace the brass. Not a fun task at any time but especially so if the weather was bad or at night and knowing you had the mainline blocked holding up other trains and their planned meets, necessitating the changing of orders all up and down the line. Other equipment included a spare knuckle, hose bags and even a wrecking chain to chain up a car that had its drawbar yanked out and drag the car behind the van to get it to a siding.

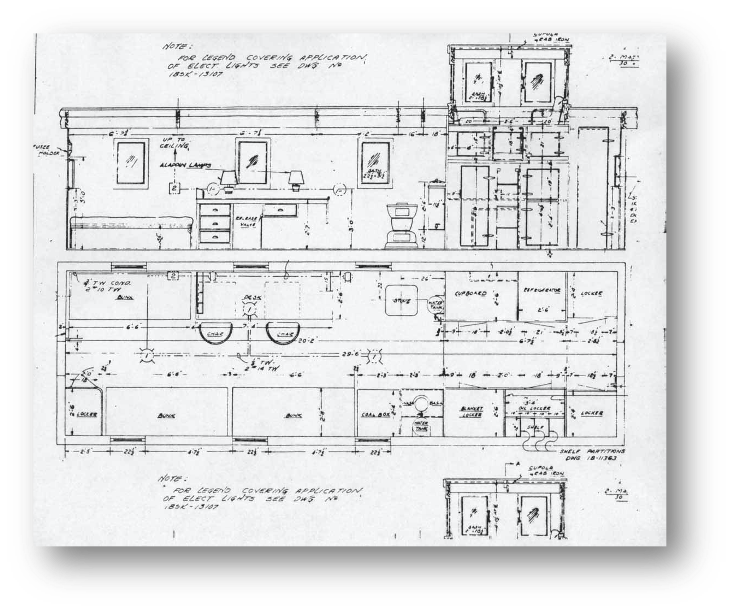

Above – Caboose diagram.

Railroading was vastly different in those days, and there’s doubt that many of today’s railroaders appreciate what their Brothers (fellow railroaders) went through every day; no radios, just hand or lamp signals to communicate with; no bottled water to drink, just tap water in a galvanized pail and some ice to sit it on (Vans had a small tank with an ice compartment); no air- conditioned private hotel rooms at the end of a run (or a limousine ride either) just a small bed in a van or a bunkhouse shared with others in a noisy, dirty yard. Few of today’s railroaders could work like their predecessors had to; they are too soft!

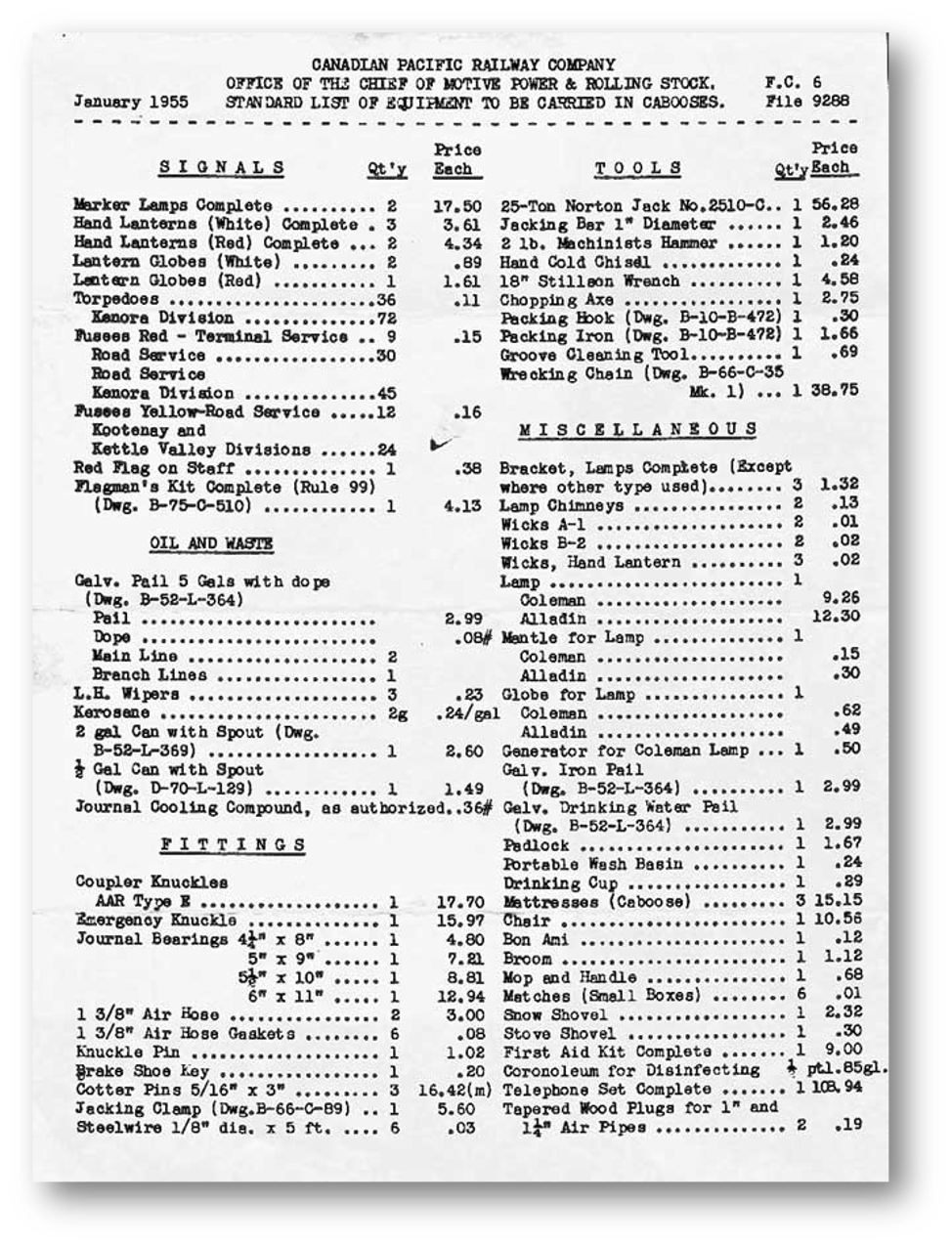

Below – Common list of equipment carried in a Caboose

Recollections on riding in a caboose

The following is an edited excerpt from an article found by Paul Brady in an issue of the Hamilton Spectator of November 29th, 1963. Originally written by a staff writer, Martin O’Malley, it graphically describes what a journey on a grain train from the Prairies to the Lakehead in a caboose was like. This is followed by a personal experience of your editor while employed in the Industrial Traffic Department of Maple Leaf Mills on Queen’s Quay in Toronto back in the early 1960’s.

Caboose Like a Mobile Padded Cell – By Martin O’Malley

Riding in a caboose is like riding in a mobile padded cell. “They’re rough,” said burly tail-end brakeman Kenny Thompson. “You’ve got to be ready all the time. They’ll run in and out. And when you run in, they’ll run out.” …shades of Knute Rockne, the famed football hero.

He was referring to the terrific jolt one receives at the rear of a freight train. When the three diesels at the “head-end” start moving they pull the box car immediately behind, roughly, six inches. And I mean roughly.

The six inches represents the slack in the coupling equipment between each car. There were 126 cars loaded with grain on our train. Multiply this by six and it feels like the harmless looking orange caboose suddenly reared up and slammed into a brick wall 63 feet away.

First Class Ticket

The chain reaction makes the jolt progressively greater further back on the train. That’s why livestock is placed up close to the diesels. The fragile human cargo needed at the back is left to fend for itself.

A passenger has to purchase a first-class ticket-$19.50 one way to the Lakehead (from Winnipeg) before he rides a caboose. And he must sign a release paper so the railway isn’t responsible for his injuries.

The inside of the caboose is a page from Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The windows are antiques, a pot belly stove sits in one corner and a water can sits in another. Lanterns go on at dusk and squat tables and chairs are nailed to the floor. “If they weren’t, they’d end up on top of you someday,” said Mr. Thompson.

A stretcher is strapped to the roof of every caboose and red-jacketed flares are strapped to the rear door. Most cabooses have mattresses everywhere-on chairs, draped over benches, in the observation “dome” (a private joke among railway men) and around everything that might get in your way.

One tangible link to the post-Sputnik age is the elaborate equipment for communication. The conductor talks freely with the engineers more than a mile ahead and the engineers converse with trains as far as thirty miles away.

The familiar picture of a conductor smiling and waving at trackside youngsters is a monument to his endurance and constitution. If only they knew what the poor fellow was going through.

Keeps Stopping

En route, the train periodically pulls off the mainline into a siding, picks up several cars, drops off a few more and keeps high-balling along. After passing in and out of the United States, we arrived in Rainy River at 9:40 p.m. Robinson, the conductor, uncoupled the caboose and while a new one rolled down the track, I had time to run across a field to a hotel to demolish a bowl of soup, ham sandwich and a glass of milk.

Each tail-end crew stays in the same caboose. A conductor earns $13.75 every hundred miles for the Winnipeg to Rainy River run, the men will get about $50.

Bed of Springs

My new conductor and brakeman were Bill Shatford and Nick Alecsijuk, both from Rainy River. I never saw the engineers from Winnipeg to the Lakehead. They were always a mile ahead of me.

The second caboose wasn’t as well equipped as the first. There were no mattresses and I slept six hours on a bed of springs.

Glynn Lyons and Lorne Valliquette, of Port Arthur, were the third caboose crew. This run from Atikokan to the Lakehead is the roughest of all because of a constantly rolling terrain.

One jolt brought a bucket of water down on me.

Mr. Valliquette was most vociferous about riding conditions at the rear of a freight train. “They should let the railway officials ride on a caboose. But no, they hook up a special shock resistant coach and the bumps and bruises go unnoticed.” He said the run to the Lakehead gets so rough that sometimes the crew has to plan ahead for meals. Like between Rock Canyon and Sandy Harbour, we’ll have fifteen minutes for lunch.

Dull, Dangerous

Then it’s back to the dome and the mattresses.

In two weeks, these injuries were recorded on the Atikokan-Lakehead trip:

-a brakeman broke his nose falling against a pipe.

-A conductor slipped a disc when he crashed into a door.

-A brakeman was taken to the hospital for nine stitches when his face went through a window.

Despite the apparent danger, caboose riding is quite dull. There is paperwork for the conductor; the usual jumping on and off to switch tracks, smoking cigarettes, small talk, waving to trackside workers and miles of steel track clicking by.

Brief flashes of the unusual provide racks to hang conversation on. Like the moose that panicked at the roar of the diesel and leapt over a fence.

On all three cabooses, I was the subject for a lot of good-natured ridicule because of my slipping and sliding and banging about the walls. My hour came shortly before we pulled into the Lakehead. Glynn was just getting up from his chair when the slack hit us. Firmly implanted in my chair, I reached over and steadied him.

“Thanks,” he mumbled gratefully.

“Hmmph” I replied.

My Caboose Ride – By Bob Holden

While employed by Maple Leaf Mills in the early 60’s, located on the waterfront at the foot of Bathurst along Queens Quay, among my duties was creating daily switch lists covering the elevator and dock sidings, and also for the Linseed Oil plant on its own pier just west of the elevators. These lists would be given to train crews who uncoupled the caboose and then would spot the cars onto the appropriate locations on our sidings, timing their work so that it was usually completed just before lunch. Once finished, they would re-couple with the caboose and head east towards Spadina along the switching yard parallel to Queens Quay to grab lunch at a restaurant located near Terminal Warehouse not far from my CIBC bank.

As I’d gotten to know the crews quite well, on paydays I was invited to accompany them and would be dropped off at the bank and then after my business was done I’d rejoin them at the restaurant for my own lunch. After lunch we’d return westward along the yard and I’d be dropped off across the street from our small office in front of the grain elevator (see the small yellowish building in the photo). The ride was away rougher than any I’d ever experienced in a railway passenger car. (At the time, I travelled by rail to see my parents in Brockville about every six weeks or so.)

The interior of the caboose was pretty sparse with a couple of benches also serving as bunks, a small desk and a pot-belied stove all securely bolted to the floor. As a young non-railroader I was good-naturedly ribbed about the daily paperwork I did for them and they’d always have a new joke to tell me. Needless to say, I would much rather stick to passenger trains for any longer journeys!!

Photo credits this page – Robert Holden; taken at the Smith Falls Railway Museum

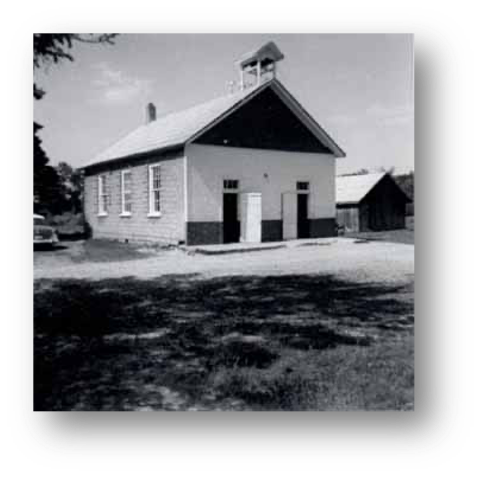

Where in Georgina?

Below is our newest mystery location. What and where is it? Our last location showed a Metropolitan radial car rounding the curve just north of Deer Park Drive in Roches Point. Dale Taylor once again correctly identified our last mystery location after the hint in December’s issue of our newsletter.

Photo from Tom Glover

News and Events

Normally in January we’d hold a General Meeting called “Bring and Brag”; an opportunity to share an historic artifact we possess with other members of the GHS. As this is not possible under the current circumstances, we ask that our members and readers send images and descriptions of these things to us so they may be shared with the membership through this newsletter. Send them to any of the e-mails listed on the ‘Contact Us’ page of this newsletter.

We are still under lockdown as declared by our provincial government due to Covid-19 and so our meetings and activities remain suspended. Hopefully, later in the New Year, these restrictions may eventually come to an end and we may once again resume our normal activities. Since we were unable to hold our usual Annual General Meeting in November, we are exploring options to hold it and our elections in a timely manner and will keep you advised as to how and when this will take place.

A reminder to all of our members; renewals for 2021 membership are now due.

The Pefferlaw Dam

The Lake Simcoe Conservation Authority Board is moving forward to transfer the ownership and maintenance of the Pefferlaw Dam to the Town of Georgina by December 21, 2021. A motion has been made by the Heritage Committee of the Town of Georgina that the council designate the Pefferlaw Dam a Heritage site.

The Johnston Cemetery Pefferlaw

The Johnston Cemetery is a small plot of land located on the main street of Pefferlaw where the Robert Johnston family have been buried since 1860. The cemetery is surrounded by an antique wrought iron fence. The Heritage Committee has recommended to the council of the Town of Georgina that a motion be passed to designate the cemetery as a Heritage site. However, an application has been made by the owners of the property to the Registrar of Burial Sites to close the cemetery and move the remains.

The Georgina Historical Society is not in favour of this action to close the site and move the remains. The Georgina Historical Society will be submitting an objection to this application to the Registrar of Burial Sites. We feel the graves of the founding family of Pefferlaw should not be disturbed but left to “Rest in Peace” in their chosen burial place.

You may voice your opinion by writing to:

Registrar of Burial Sites

Consumer Services Operations Division

Ministry of Government and Consumer Services

56 Wellesley Street West, 16th Floor,

Toronto, ON

M7A 1C1

Email Nancy.Watkins@ontario.ca

We appreciate your support in this matter.

Tom Glover