Click to Download the PDF

Download the Word Doc

President’s Message

March is upon us, spring is just around the corner, and we’re seeing the buds and plants starting to come out already. It won’t be long before we’re complaining that it’s too hot! The Georgina Historical Society is entering it’s fiftieth year as a not-for-profit charitable organization, and it’s fifty-sixth year as a Historical Society. As a group of committed volunteers based in Sutton, a lot of their early energies were focused on preserving the historic buildings of Georgina, culminating in the Georgina Pioneer Village that we know today. Without the work of these dedicated volunteers, historically significant buildings such as the Noble House, the Sutton Railway Station and the Mann House would be lost to the wrecker’s ball with only a few pictures left to remember them by, and the location of the Georgina Pioneer Village would still be just a muddy field.

But we also cannot forget the original objective of the Society, which is to discover and collect any material or objects which illustrate the history of the area, provide for the preservation of such material, and to disseminate such information. I would be remiss if I didn’t identify the people who attended that first meeting of our Society. Listed on the original proposed constitution for the “Lake Simcoe South Shore Historical Society”, forwarded to me by Estelle LeMaire and dated April 17, 1968, I find the following names; Bob Luke, Nina Marsden, Mr. and Mrs. Doug Clarke, Mrs. Seal, Mrs. Morrison, Georgia Lyons, Marion Gillan, Mercielle Burrows and Isobel Greer. Those were the first, and countless other dedicated volunteers have carried the GHS banner for the last fifty-six years, celebrating Georgina’s rich and diverse history.

On the subject of our Society, I want to thank you all for volunteering your time, energy and financial assistance to keep the Georgina Historical Society a valuable, and valued, part of the diverse fabric that makes up our community.

And finally, I am looking forward to attending Sarah Harrison’s presentation about a very interesting industry that flourished a long time ago, coming up on Tuesday March 18, the first day of spring, at the Georgina Centre for Arts and Culture, at 149 High Street in Sutton. As always, we open the doors at 6:30 for meet and greet, with the presentation starting at 7pm. I’m hoping to seeing you all there.

Paul Brady, President

Why do we have daylight savings time?

Submitted by Lena Thorogood for publication in the Newmarket Historical Society newsletter for March 2024.

Many think that daylight saving time was conceived to give farmers an extra hour of sunlight to till their fields, but this is a common misconception. In fact, farmers have long been opposed to springing forward and falling back, since it throws off their usual harvesting schedule.

The real reasons for daylight saving are based around energy conservation and a desire to match daylight hours to the times when most people are awake. The idea dates back to 1895, entomologist George Vernon Hudson unsuccessfully proposed an annual 2 hour time shift to the Royal Society of New Zealand.

Ten years later, the British construction magnate William Willett picked up where Hudson left off when he argued that the United Kingdom should adjust their clocks by 80 minutes each spring and fall to give people more time to enjoy daytime recreation. Willett was a tireless advocate of what he called “Summer Time,” but his idea never made it through Parliament.

The first real experiments with daylight saving time began during World War I. On April 30, 1916, Germany and Austria implemented a one-hour clock shift as a way of conserving electricity needed for the war effort. (While Germany and Austria were the first countries to implement daylight savings, the first towns to implement a seasonal time-shift were Port Arthur and Fort William, Canada in 1908.)

Pioneer Farming and Agriculture – Part One

By R. W. Holden

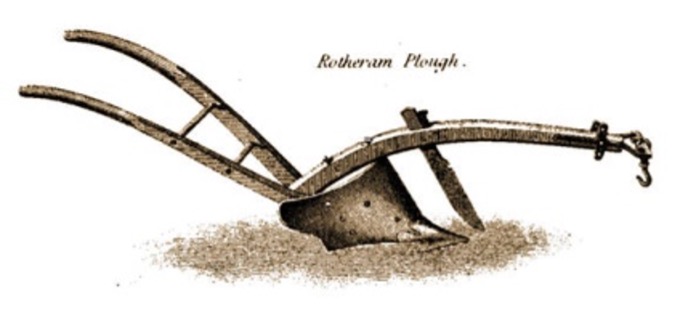

Georgina has long history of farming and agricultural production. With approaching spring weather, we thought it might be interesting to examine pioneer farming and the tools used prior to the advent of mechanized agriculture in modern times. Early pioneers worked hard, often from before dawn until after dusk during the growing season preparing their fields, planting seeds, maintaining the land, and finally, reaping in their crops. Always hopeful that the elements would co-operate to ensure an adequate reward for their efforts, that was not always the case. Mother nature often had other ideas.

Anyone who has had the opportunity to plow a field behind a horse-drawn walking plow knows just how hard the work was; I was given the opportunity to do a field like that as a teenager by a friend of my father who, piqued by my interest in history, thought that I should experience it first-hand. It was hard physical labour! …and God help you if you happened to catch a hidden rock or boulder in the soil! My arms and shoulders ached from my efforts for several days afterwards.

All the farm implements of the early days were made by hand, the wooden part being made by the farmer himself, and the iron part usually by a local blacksmith. The implements used by the pioneers were few and simple compared with those used by the farmers today. In addition to the spade, hoe and rake familiar to modern gardeners, early hand tools used in farming included the seeder, a perforated wooden trough carried by means of a strap around the neck and used in broadcast seeding; the sickle and the scythe, one- and 2-handed knives, respectively, used for cutting field crops and hay;the flail, 2 wooden rods attached by a strap and used to thresh out the kernels of grain; the winnowing tray, a 2-handled, half-moon-shaped receptacle used to cast flailed grain into the air so that the chaff could be blown away; the fork, used for pitching hay or shovelling manure; the wooden grain shovel; the hay knife and hay hook; and the grafting froe, a knife used to split branches in grafting. Most of these implements were superseded; others (eg, the plow) underwent substantial modification.

As larger fields were cleared out, the principle farming implements used became the plough, harrow, cradle, sickle, rake, scythe and roller.

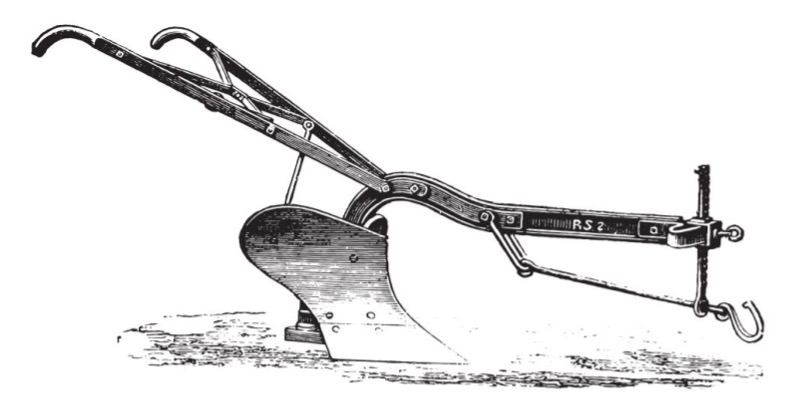

From wooden-moldboard, single-handled, home-made machines, plows became chilled-steel, mass-produced, scientifically designed 2-handled walking plows; then single-moldboard riding plows, double-moldboard riding plows, and finally giant machines with up to 16 moldboards. These alterations occurred as the source of power changed from oxen (best for root-strewn pioneer farms) to teams of horses, then to multiple teams of horses (up to 16 to a hitch), to steam-driven traction engines with the power of 50 or more horses, and finally to lighter, more versatile but equally powerful gasoline or diesel tractors.

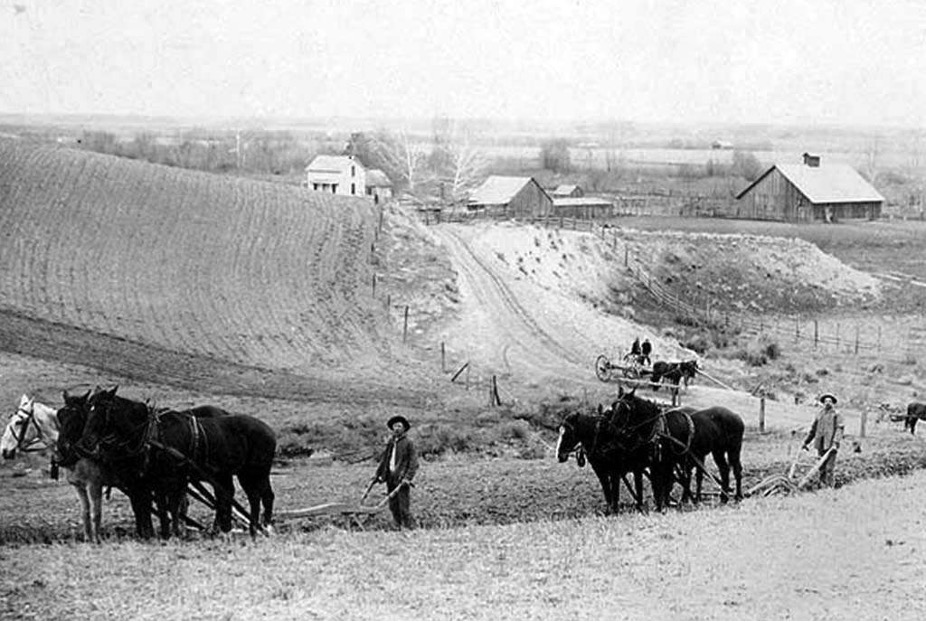

Many improvements have been made in the plough over the years. The first plough was made of wood (usually a piece of bent oak), and covered with iron. Some very rude ones were made out of a natural crook, as the root of a tree; others had wooden mould boards and iron points.

Harrows were used to break up the clods of soil after plowing. The first harrows used in the backwoods clearings were the “three-cornered drag,” a V-shaped framework of wood, with cross-pieces and fitted with iron teeth. It was often made out of the crotch of a tree, holes being bored for the iron teeth. This kind of harrow was particularly well adapted for working up the soil in the stumpy ground, as on account of its shape, it did not catch on to the stumps so easily as the square harrow.

A Square Harrow

The “brush” or “bush” harrow, made of a bunch of brushwood, was sometimes made to answer the purpose of a harrow in the loose soil of the new ground, which very often did not require any ploughing at all the first time cropped. In the cleared ground, the square harrows, made of wood with iron teeth, were used. These were afterwards made in two parts and hinged together. This kind of harrow has been almost entirely superseded by the harrow made of steel.

The only kind of rake was the wooden hand-rake; later on, the wooden lift-rake, and the wooden dump- rake, drawn by a horse, came into existence. The farmer walked behind and held the handles until sufficient hay had been collected, when he would lift or dump it in rows. These rakes were followed by the sulky-rake now in use.

For levelling off the lumpy ground the farmer had a roller, made out of a heavy log of wood, with a tongue attached to it, to hitch the horses to. The minor farm implements were the long-handled shovel and spade and the pitchfork, the hoe and garden rake, all very heavy and clumsily made of iron, while nowadays such implements are made of steel, and consequently much lighter and better finished. There were wooden forks for pitching straw. The manure forks were generally made with broad tines and very heavy.

The old farm wagon had wooden axles with a strip of iron above and below, to prevent the wood from wearing away. They were greased with tar, made from the pitch got from’ the pine trees, and mixed with lard in the winter time, to prevent it from becoming too thick. The tar was kept for the purpose in a special bucket, which was hung underneath the back of the wagon when on a long journey.

The wheels of the old “lumber” wagon were kept in place by linch-pins, which were dropped through a hole in the end of the axle, but as they did not secure the wheel very tightly when the wagon was in motion, they made a rattling noise, which could be heard for quite a distance away. There being no iron wagon springs, the seat was perched on the end of two poles with the ends fastened in the wagon box. This “spring-pole” wagon-seat, although high up in the air, was the most comfortable one known. Later wagons used wheels with metal tires and were similar in every way to the wagons used on the road of the day.

https://www.electricscotland.com/history/pen/chapter16.htm

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/agricultural-implements

Where in Georgina?

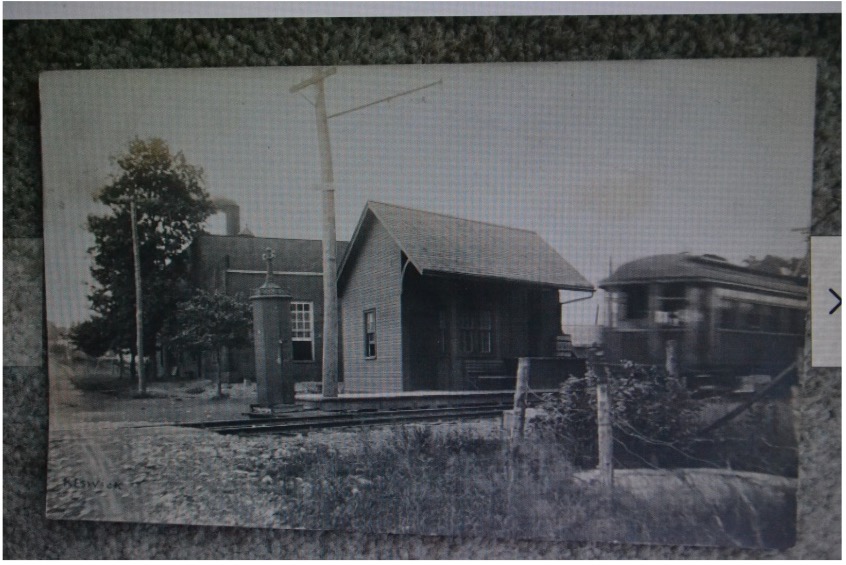

Our last mystery location was identified correctly by our President Paul Brady. Thanks Paul! It’s finally solved…it was the Orchard Beach General Store! We have a new mystery location below …where is it, and what is it?

Our Pioneer Ancestors

Adapted from Might’s Directory of 1892-1893 p. 1236 Toronto, Ontario. Below are listed the businessmen in the village.

BALDWEN. A village on Black river (which supplies power), in Georgina Township, York Co, 50 miles north of Toronto, the county seat, and 4 miles southeast of Sutton, on the Northern district of the Midland division GTR, its nearest railway point. 7., Newmarket, 20 miles southwest, is the nearest bank location. It has a flour and saw mill and contains Bible Christian and Methodist churches and a public school. Pop, 300. Mail daily. W L Crittenden, post master.

Conner S, butcher

Crittenden P, general store

Crittenden W L, Hotel and Postmaster

Draper Nelson, blacksmith

Grylls Charles, painter

Heise Wm, flour mill

Pringle Charles, general store

Tomlinson George, planing mill

Yeates Thomas, saw and planing mill and general store

Your Board for 2024

Photo by Karen Wolfe

From left to right; Bob Holden, Gail Moore, Dee Lawrence, Sarah Harrison, Paul Brady, Kim Brady, Widit McLean, and Tom Glover. Missing: our new director Stella Trainor.

Did you know?

Hot water turns to ice faster than cold water. The British philosopher Francis Bacon may have said it first, some four centuries ago, but it took an Innisfil native to actually prove it scientifically. In 1970, Dr. George Kell, a chemist with the National Research Council of Canada and brother of William M. “Bill” Kell, found that hot water freezes 10 percent faster than an equal amount of cold water when it’s 20 degrees (ºF) outdoors.

—from an article in the Toronto Star, February 25, 1970 and republished in the March 2024 issue of the Innisfil Historical Society newsletter.

News

Help!! We still need additional directors. If you are interested in playing a role in the work we are doing, don’t hesitate to contact us. Sarah Harrison resigned from our Board as she has just accepted a full-time library position and will be unable to participate as fully with us. She will remain an active member of the GHS. Thank you for your excellent service Sarah!

The digitization strategy for the Archives has been approved by Georgina Town Council and may now be downloaded for viewing from the following website:

The Town of Georgina has accepted the recommendations of the document named “The Pioneer Cemeteries Management Plan”, an eighty page report prepared by LEES and Associates Consulting Ltd. Town Staff has recommended that council accept the report and implement the plan. This will mean that our long-neglected heritage cemeteries will start to get the attention they deserve, slowly bringing them up to a standard that we can be proud of. The Georgina Historical Society hopes to play a role in their rehabilitation, doing volunteer work on cutting back over-grown bushes and other tasks. If you are interested in helping out with this work, please contact a Board member.

We have also commenced initial planning for Harvestfest this upcoming September. We’re trying to bring in some new and interesting exhibits, demonstrations, and attractions to the event, and will be needing volunteers to help us out. So if you can help in any way, please contact any member of the board.

Events

Tuesday, March 19, 2024 – general meeting at the Georgina Centre for Arts and Culture. 6:30 meet & greet, 7:00 PM meeting; Sarah Harrison will give a presentation on the Frog Leg Industry of the Holland River.

Tuesday, April 2nd – Next Board meeting at the Schoolhouse in Georgina Pioneer Village 2:00 PM

May 9th & 10th (Thursday & Friday) – Georgina Pioneer Village. Rise to Rebellion

Saturday, June 1st – Opening week-end of Georgina Pioneer Village