Click to Download the PDF

Download the Word Doc

President’s Message

Spring is here and as always there is need for help to tidy up the village for spring visitors. If you would like to offer your services contact Melissa at the Pioneer Village. We have booked a booth at the Georgina Home Show to promote the Georgina Historical Society and the Pioneer Village. If you have time on May 4 or 5 we would appreciate some help in the booth. All Georgina residents need to realize the importance of preserving, protecting and promoting our history.

~ Tom Glover, President

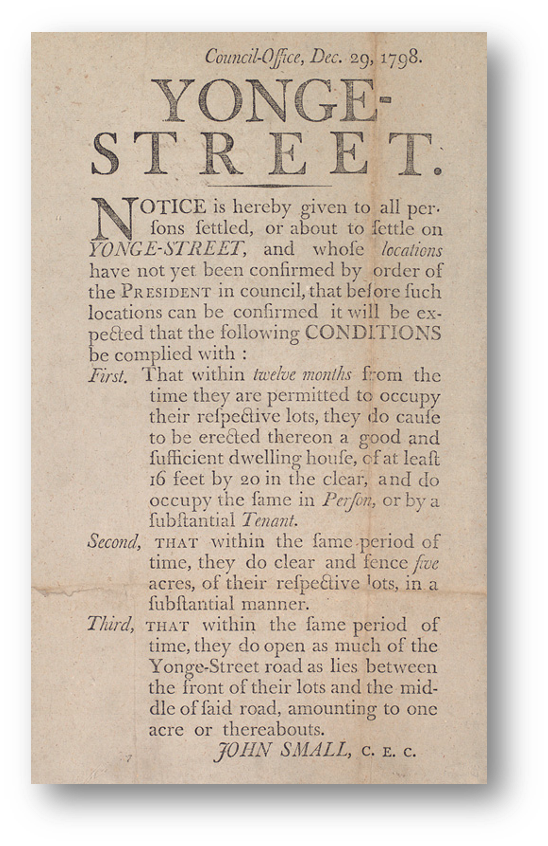

Travelling Early Roads – By R. W. Holden

Earliest roads in Georgina often wandered through the forest around and over tree stumps as pathways were cut through the dense forest from one clearing to the next. While early surveyors mapped and laid out townships for settlement, it did not always follow that their nicely organized plans forming an imaginary grid upon the landscape would automatically reveal themselves as geometric pathways from one place to another. One of the settlement duties of first arrivals upon the land was to clear the front of their property to create a road allowance. This was not always completed on time and never done on lands not taken up for settlement. In addition one out of every seven lots in early Upper Canada was set aside as a Clergy or Crown Reserve and left vacant. There were also a large number of lots, especially in back townships, with absentee owners. So unlike along main roads such as Yonge Street, the Dundas Highway, or Danforth Road, road allowances were inconsistent and poorly developed. Besides, the former were surveyed, developed and built as key transportation routes without waiting for settlement duties to be completed, while the latter were more often than not blazed trails.

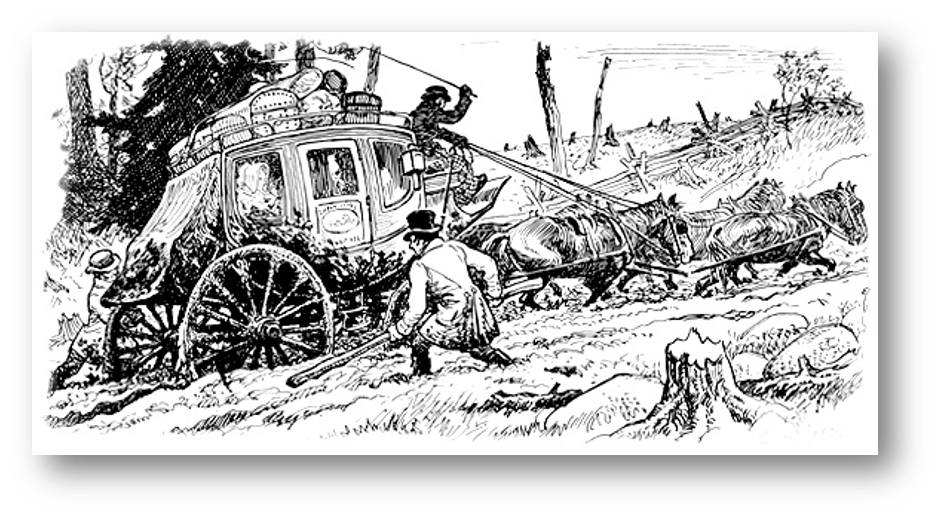

By the 1830’s, the first macadamized roads were constructed with a proper substrate of gravel and ditching to drain away surplus moisture. Macadamization was invented in Britain by Scottish engineer John Loudon McAdam around 1820, in which single-sized crushed stone layers of small angular stones are placed in shallow lifts and compacted thoroughly. A binding layer of stone dust (crushed stone from the original material) may form; it may also, after rolling, be covered with a binder to keep dust and stones together. The method simplified what had been considered state of the art at that point. In Upper Canada, a form of macadamization was done by laying and compacting successive layers of broken stone, and crushed gravel sometimes with a top layer asphalt or hot tar, though the latter was only seen in the largest communities and only on the most important roads almost until the twentieth century. Roads began to improve slowly, but only on major thoroughfares. Paving was unknown. As late as the first decade of the twentieth century, images of horse-drawn wagons may be found mired to their axles in mud. The only alternative to inland travel was to be situated on a major water route using sails, oars or paddles, though some ferries were powered by treadmills using horsepower.

Winter and the dry hot days of summer were the best times to travel. Then the roads would be hard-packed earth or frozen. In winter, you didn’t need to always follow the roads except in forested areas; it was possible to slide across open fields in a sleigh. The ride was quicker and much smoother. Spring was the worst for travel. As the snow melted and the frost came out of the ground, the roads would heave; soft mud entrapped the narrow wheels of carts, wagons, and carriages ensuring a long uncomfortable journey to be avoided as much as possible. Corduroy roads of logs over swampy land would heave up often causing broken axles and wheels.

Public transportation soon followed once a road was put into place. One of the earliest performing this service was George Playter along Yonge Street. Teamsters and stages would soon ply their trade on major roadways between communities, but that is a story for another article!

References:

- https://www.electriccanadian.com/history/ontario/ontario/ontario5.htm

- https://www.electriccanadian.com/history/ontario/ontario/ontario5.htm

- https://www.electriccanadian.com/history/ontario/ontario/ontario5.htm\

- Image one: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Notice_to_settlers_on_Yonge_Street_1798.jpg

- Images two and three: https://www.electriccanadian.com/history/ontario/ontario/ontario5.htm

- Image four: https://www.dalzielbarn.com/pages/TheFarm/ComeToCanada.html

Also consulted: The Story of Canadian Roads, by E.C. Guillet, University of Toronto Press 1967

The Ice Industry and Jackson’s Point – By Paul Brady

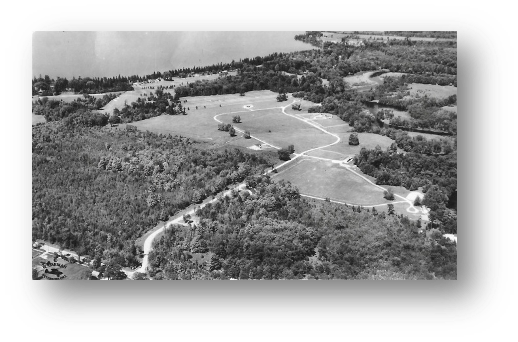

A hundred and fifty years ago, the Lake Simcoe Junction Railway came to the Point, creating the ability to ship ice from Lake Simcoe. A wharf was constructed which went out into the lake, allowing the ice to be loaded directly into the rail cars. This wharf entered the lake in the Jackson’s Point Harbour, right where the sail boat docks are now, and was long enough to allow four freight cars onto it.

Lake Simcoe was a reliable source, usually freezing up in December and making ice through to March, and the ice was considered to be 100% pure. Getting that ice out of the lake was not an easy job, but resulted in a huge industry that, at its peak, employed about fifty people and several teams of horses in Jackson’s Point alone. The ice was shipped all over southern Ontario and into the northern states.

The Springwater Ice Company was formed in 1876 to cut ice from Lake Simcoe. The name was changed to the Lake Simcoe Ice and Fuel Company, which is the company most commonly associated with Jackson’s Point. Another company that was identified with Jackson’s Point was Knickerbocker Ice, which was absorbed by Lake Simcoe Ice in 1914.

It is interesting to note that ice was commercially harvested at only four locations on Lake Simcoe. These sites were Jackson’s Point, Belle Ewart (the “e” was added to Belle because it classed the place up a bit), Barrie and Orillia. The reason for this is because these four places are the only spots on the lake that rail lines accessed the lake, and the rails were the only economical way to get such a heavy and perishable commodity such as ice to the markets.

Ice harvesting was a dangerous business. The water beneath the ice was deep and cold, and a slip or misstep could spell disaster. Most blocks measured 22” (56cm) by 32” (80cm), and could weigh as much as 300 pounds (135kg). Originally the blocks were cut by hand with a long sharp saw, much like a lumberjack saw but with only one handle. As the turn of the century approached, mechanical devices were created to speed up this back-breaking work. A channel was cut in the ice so that the ice blocks could be floated to the shore, or the blocks were attached to a team of horses that would haul them out of the water.

As many as forty rail cars could be loaded on a good day. The rail cars were insulated with bales of hay, and it must have been quite a sight to see the locomotives (described as being “like a two headed monster, fiery dragon, belching sparks and billows of black smoke from both its huge smokestacks!”) as they struggled to get their burden moving along Lorne Street to the flats along what is now Grew Boulevard.

There were huge ice houses in which to store the ice all around the Point. These buildings could be as big as 100 feet long by 30 feet wide and 30 feet tall. Specialized lifts were created to facilitate loading the ice onto the rail cars or into the ice houses. Each one of the local hotels and restaurants had their own small ice house that was stocked with ice in the winter. All of this industry centered around 20 Bonnie Blvd. and Bonnie Park/Lorne Park and was a reliable source of employment for the local population for many decades.

The ice industry was a perfect complement to the existing lumber industry, as sawdust from the lumber mill was used to insulate the ice, and workers employed in the ice industry all winter transitioned to work in the lumber business in the summer. With a lumber mill at 20 Bonnie Blvd., the Lake Simcoe Junction Railway servicing Jackson’s Point, and 100% pure ice being produced all winter, this industry had a near perfect set of conditions.

As with all things, demand slowly fell off as the Lake Simcoe Ice Company, which was headquartered in Toronto, started to produce their own artificial ice. The company used the name “Lake Simcoe Ice” long after their product was artificially made in Toronto, trading on the fact that our ice was considered to be the best in the world. Slowly the industry died out, the ice houses were dismantled and Jackson’s Point started to capitalize on the tourist trade, as “Ontario’s first Cottage Country”.

News and Events

We will be participating in a garage sale held on May 11th at the Ice Palace in Keswick to help raise funds for the Georgina Historical Society. The hours of the sale will be from 9:00 AM to 1:00 PM, and set up will take place at 8:00 AM. If you have items you can donate for sale or would like to volunteer some time manning our tables, please contact Joel Foote at (905) 722-8569 or you may e-mail him at jlarryfoote@hotmail.com.

Dates to Remember

Next Board Meeting: Monday, May 6th, Noble House @ 1:30PM

Georgina Home Show: May 4th and 5th in Keswick. Volunteers needed for the booth!

Community Garage Sale: May 11th, Georgina Ice Palace, Keswick from 9:00 AM to 1:00 PM Set up at 8:00 AM.

Rise to Rebellion: May 9, Georgina Pioneer Village

May General Meeting: May 21st, Subject & venue to be decided

Canada Day: July 1st

Harvest Fest: September 14th

Old Fashioned Christmas: November 28th

Where in Georgina?