Click to Download the PDF

Download the Word Doc

President’s Message

Summer is fast approaching, but you’d never know it tonight. Windy and cold with a bit of snow in the air, we got spoiled with the false spring of a few weeks ago. Oh well, nearly there now.

We want to thank Dee Lawrence and Sarah Harrison for their years of service on the board of directors of your Historical Society. Both are moving on to other things, leaving some big shoes to fill. If you want to become more involved with your society, we have several positions on the board of directors that are available.

On other matters, Georgina’s historic buildings are becoming endangered as property values rise and the cost of renovation becomes prohibitively expensive. One of Georgina’s more important Georgian style homes, built in the 1850’s and once belonging to John Morton, a former Reeve of North Gwillimbury, has had a demolition permit issued, and is slated to be replaced by a modern dwelling. This unfortunate situation points up the importance of a strong Heritage Advisory Committee, the purpose of which is to advise Town planners about historic properties. The Georgina Heritage Advisory Committee was disbanded after the last municipal election, and for the first time since 1972 this volunteer group hasn’t played a role in the Town’s plans. An engaged group of concerned citizens met on April 4 to discuss these very problems, and a delegation was formed to bring attention to this situation. They will present the matter to council.

On a happier note, the Town of Georgina is moving ahead fulfilling its duties as caretakers of Georgina’s pioneer cemeteries. The consultant’s report is done and the Town is following the road map laid out by these experts, to bring the cemeteries up to an acceptable standard. With some of the richest history in Ontario right at our doorstep, the Georgina Historical Society is looking forward to participating in this project by sponsoring explanatory signage and guide boards for placement at the cemeteries.

I want to thank the staff and volunteers at the Georgina Centre for Arts and Culture for letting your society use their beautiful space for our general meetings over the winter, and also to once again thank our presenters who entertained us on those evenings. Who knew that there was so much to learn about frogs?

We’re back to the Georgina Pioneer Village for our general meeting this month, April 16, and Melissa Matt, our excellent Village curator, will be speaking of winter sports in Georgina in years gone by. I hope to see you all there,

That’s it for now,

Paul Brady, President, Georgina Historical Society

MOONLIGHT ON GRAVE PRETTY, LIVES IN CEMETERY VAULT

By Ben Rose, Star Staff Reporter

Here’s a fascinating human interest story about a Sutton resident, handyman and grave digger Cecil Smith, brought to us by Richard Munro. Written sometime in the later fifties or early sixties, it is a kind of sad story, giving a fascinating insight into the mind of Cecil and simpler times. Mr. Smith was an older man who lived around the Sutton area sometime in the mid-fifties or sixties. Housing seems to have been a problem then too!

Paul Brady was talking to a local Sutton resident about Mr. Smith a while ago, and they told him that they recalled their father taking firewood to Mr. Smith when he was living in a small cabin on the Sutton fairgrounds. Mr. Smith was so pleased with the gesture that he told the friend’s father “That’s so nice of you, I’ll dig your grave extra deep.” Ed.

Sutton, Sept. 20-

Cecil Smith, 50, bachelor resident of this village, has a solid brick home all to himself, rent free. The only trouble is that it’s in a cemetery vault!

“It’s all on account of the housing shortage,” said Smith, a short husky man with a face beaten brown by the wind and sun. “I can’t find any place to live in town, so I live out here where nobody bothers me.”

His “home” is a picturesque almost circular little red building near the entrance to Briar Hill cemetery where, when necessary, bodies are kept overnight pending burial and where the grave diggers’ spades and shovels are stored. There are graves within a few yards of his doorway.

This is right handy for Smith. Among other jobs he does in the village, he is also the caretaker and gravedigger for Briar Hill and other cemeteries.

“There aren’t any complaints, are there?” he asked anxiously when a reporter called. “I’ve been living here since July and I like it fine. The only trouble is it’s getting cold and there is no way of heating it. There are no windows so I just leave the door open at night for air, but I can’t do that in the winter time.”

Smith unlocked the door under a sign reading “Briars Hill, 1914,” and said “Come on in.” The vault was one circular room, containing a single cot and mattress, and at least 20 spades and shovels lined up at the head of the bed. An old brown coat was his blanket. He lights the room by flashlight and in the odd moments plays on a mouth organ.

“The cemetery board doesn’t like the idea of me living out here too well, but they know I haven’t another place to go,” he said.

“I like coming out here at nights. The moonlight shining on the stones is real pretty. And in the morning the sun is shining on them and that’s pretty too; matter of fact, I like the sunshine better.”

Pioneer Farming and Agriculture – Part Two

By R. W. Holden

This is the second of a series of articles on Pioneer Agriculture. In the first part of this series, we dealt with the basic tools of the pioneer farmer. This month we will look at the developments of equipment used to facilitate seeding and harvesting a crop. Ed.

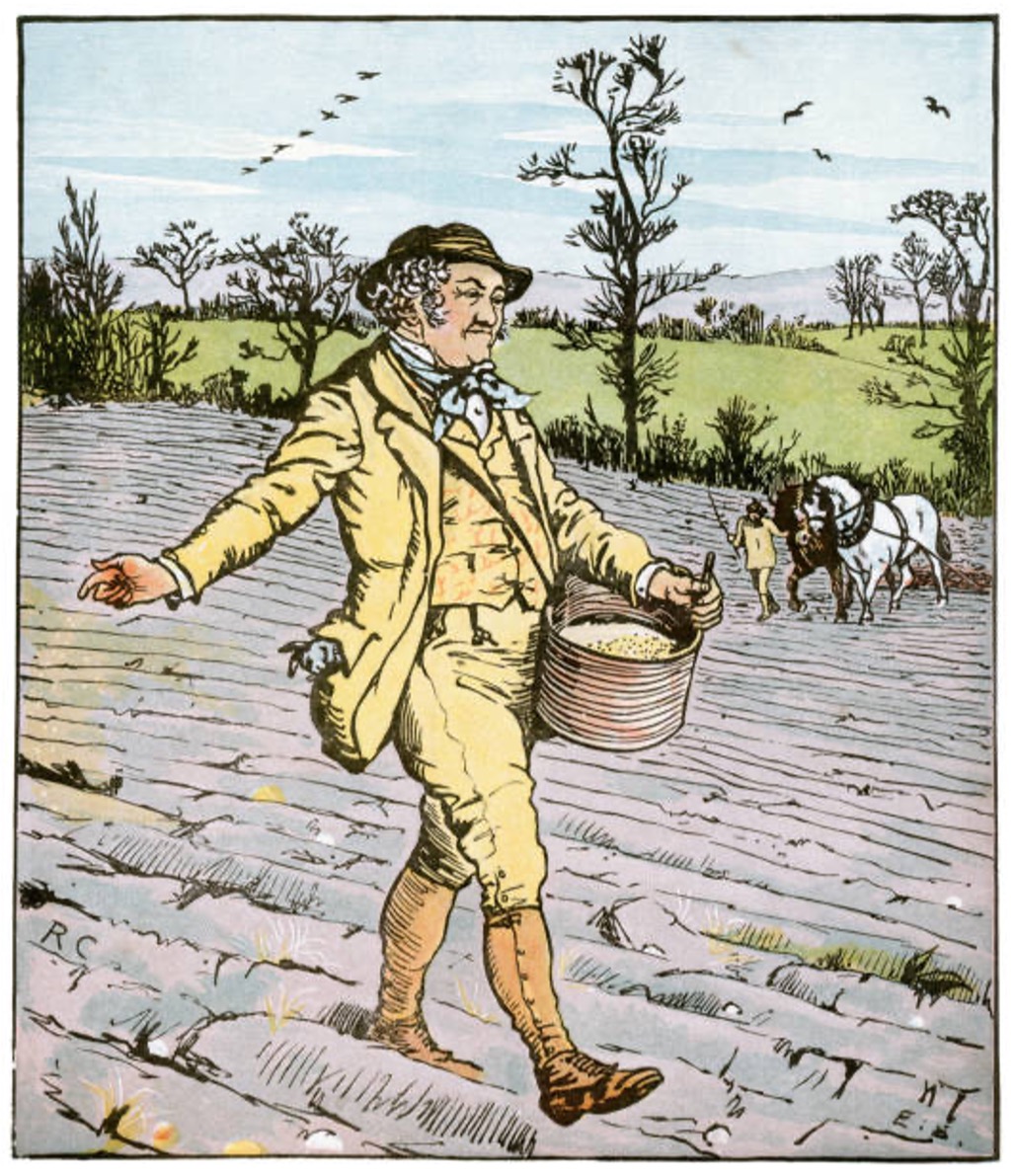

Sowing the Grain

In older methods of planting, a field was initially prepared with a plow to a series of linear cuts known as furrows. The field was then seeded by throwing the seeds over the field, a method known as manual broadcasting. The farmer in sowing his grain had a sack tied around his body and as he walked over the ground he scattered the seed with a sweep of his hand. This method of sowing grain was common for centuries.

Unfortunately seeds were not always sown to the right depth nor the proper distance from one another. Seeds landing in the furrows were better protected from the elements, and natural erosion or manual raking covered them while leaving some exposed resulting in a field planted roughly in rows, but having a large number of plants outside the furrow lanes which did not grow properly. Seeds outside the furrows were exposed to the elements or were consumed by birds or other animals wasting some seed reducing the potential crop yield. The solution to the problem was the seed drill.

The seed drill employed a series of runners spaced at the same distance as the plowed furrows. These runners, or drills, opened the furrow to a uniform depth before the seed was dropped. Behind the drills were a series of presses, metal discs which cut down the sides of the trench into which the seeds had been planted, covering them over.

This innovation permitted farmers to have precise control over the depth at which seeds were planted. This greater measure of control meant that fewer seeds germinated early or late and that seeds were able to take optimum advantage of available soil moisture in a prepared seedbed. The result was that farmers were able to use less seed and at the same time experience larger yields than under the broadcast methods.

The Babylonians were known to have used primitive seed drills as early as 1400 BCE, though the invention never reached Europe. Multi-tube iron seed drills invented by the Chinese in the 2nd century BCE gave China an efficient food production system allowing it to support its large population. This multi-tube seed drill may have been introduced to Europe following early contacts with China. In the Indian subcontinent, the seed drill was widely used among peasants as early as the 16th century. The first known European seed drill was attributed to Camillo Torello and patented by the Venetian Senate in 1566. However, seed drills of this and successive types were both expensive and unreliable, as well as fragile. Seed drills would not come into widespread use in Europe or America until the mid to late 19th century, when manufacturing advances such as machine tools, die forging and metal stamping allowed large scale precision manufacturing of metal parts. Early drills were small enough to be pulled by a single horse, and many of these remained in use into the 1930s. The availability of steam, and later gasoline tractors, however, saw the development of larger and more efficient drills that allowed farmers to seed ever larger tracts in a single day.(1)

Harvesting

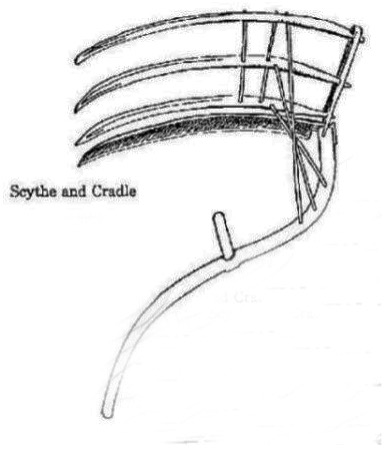

In the early days of the country all the grain was cut by means of the scythe or sickle, a curved knife a couple of feet long, with indented teeth. This was the only kind of harvest instrument the farmer had for years for cutting grain, the cradle being then unknown. Cutting a field of grain with it was a slow, tedious, and a very tiring process. With all hands on the farm to help, harvesting was soon accomplished.

Frequently planted in stumpy ground with a hoe or rake, when ripe it was cut with the sickle, bound in sheaves, and taken on the jumper to the threshing-floor, which was often no better than a big flat stone, sometimes a floor of boards, and sometimes even the bare ground, tramped hard and smooth, where, by means of the flail, or “poverty-stick” (two pieces of hardwood united by leather), the heads were pounded until the grain was all threshed out. It was then “winnowed,” or cleaned, by pouring from one vessel to another in the wind, until it was free of the chaff, after which several bags were put across a horse’s back and sent to the mill—often fourteen or fifteen miles or more distant—to be ground into flour, the farmer having to wait patiently his turn for this to be done, and which sometimes kept him from home for several days together.

It was not an uncommon thing for some of the old settlers who had no horses to have to carry the bags of wheat to the mill on their backs for long distances of fifteen or twenty miles. The first mills were situated on some stream or creek, where water-power could be obtained, as there were, of course, no steam mills then in the country. These water-power mills were relatively scarce, people sometimes traveled up to forty and fifty miles round trip to get their grists ground. Hand mills for grinding wheat were furnished by the Government to the U. E. Loyalists, and those who did not have these hand-mills would burn a hole in the top of a white oak stump; into this hollow, when well scraped out, they would place the wheat or corn and grind it into a coarse meal with a pestle made out of a piece of hard wood. This was probably in imitation of the Indian method of grinding their corn in stone cups or bowls. To facilitate the operation the pestle was sometimes fastened to the end of a spring pole extended over a forked stick stuck in the ground. The first crop of the settlers usually consisted of a field of wheat and peas, with a small patch of potatoes, pumpkins and corn.

A Square Harrow

Following the sickle came the cradle, which consisted of a framework or “rigging” of wood for gathering the grain together as it was being cut, fixed to the scythe, an instrument which previous to this time had only been used for cutting grass. The farmer, with a sweeping stroke of his brawny arms, would cut down a “swath” of from four to six feet in width. The binders (men and women) would follow with their rakes and, after raking enough together for a sheaf, would twist a handful of the stalks into a strand and bind up the bundle. An expert cradler could cut as much as three or four acres of good standing grain in a day, about as much as three or four men could bind. After the grain had been bound it was gathered together and stood on end, two sheaves in a pair, in “stooks” or “shocks” of ten or twelve sheaves, to dry.(2)

The cradle was superseded by the reaping machine, which has been the subject of many improvements up to the present time, since its introduction in 1831, when a man walked behind and raked the grain off the table as it was being cut. In 1845 a seat was made for this man at the rear of the machine, and in 1863 a self- raking attachment was added, until now we have machines which not only cut the grain but also bind it into sheaves as well. The advent of the reaping machine is a striking illustration of the truth of the old saying, “Necessity is the mother of invention.” The inventor, who lived in the Western States, saw the need of a machine that would cut the grain in the big fields of the western country just opening up to settlement more rapidly than it could be done by the old methods. This idea of saving labor has been carried out with all kinds of work, until now there is scarcely any department of labor in which machinery does not do the bulk of the work.(3)

Threshing machines or a thresher is a farm implement designed to separate grain seeds from their stalks and husks by beating the plant to make the seeds fall out. Before such machines were developed, threshing was done by hand with flails: cumbersome, very laborious, and time-consuming work, occupying one-quarter of all agricultural labour by the 18th century. In 1850 most farmers cut their grain with cradle scythes, with the few short weeks of the harvest dictating the amount grown. In winter, cut grain was threshed on the barn floor, by beating with flails or treading with horses’ hooves until the kernel fell free of the straw and was scooped up and winnowed, by the wind or by an artificial wind created by a fanning mill. Mechanization of this process removed a substantial amount of drudgery from farm labour.

The first threshing machine was invented circa 1786 by the Scottish engineer Andrew Meikle, and the subsequent adoption of such machines was one of the earlier examples of the mechanization of agriculture. During the 19th century, threshers and mechanical reapers and reaper-binders underwent the most dramatic and expensive changes gradually became widespread and making grain production far less laborious.

More efficient machines (eg, the generation of reapers triggered by the inventions of Cyrus McCormick and Obed Hussey in the US and Patrick Bell in England) allowed farmers to harvest larger and larger amounts of grain. Larger threshing machines, initially powered by one- or 2-horse treadmills, and later by immense steam-driven traction engines, began to appear. Mechanical threshers were manufactured by Waterloo, Sawyer-Massey, Hergott, Lobsinger, Moody and other Canadian manufacturers. (4)

Footnotes:

(1) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seed_drill and https://historylink101.com/lessons/farm-city/seed_drill.htm

(2) https://historylink101.com/lessons/farm-city/cradle_reaper.htm

(3) https://historylink101.com/lessons/farm-city/reaper_1.htm

(4) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Threshing_machine#

Other sources:

https://www.electricscotland.com/history/pen/chapter16.htm

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/agricultural-implements

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seed_drill

Saskatchewan Western development Museum – Teacher’s Handbook

https://www.iowapbs.org/iowapathways/mypath/2683/plowing-past-look-early-farm-machinery

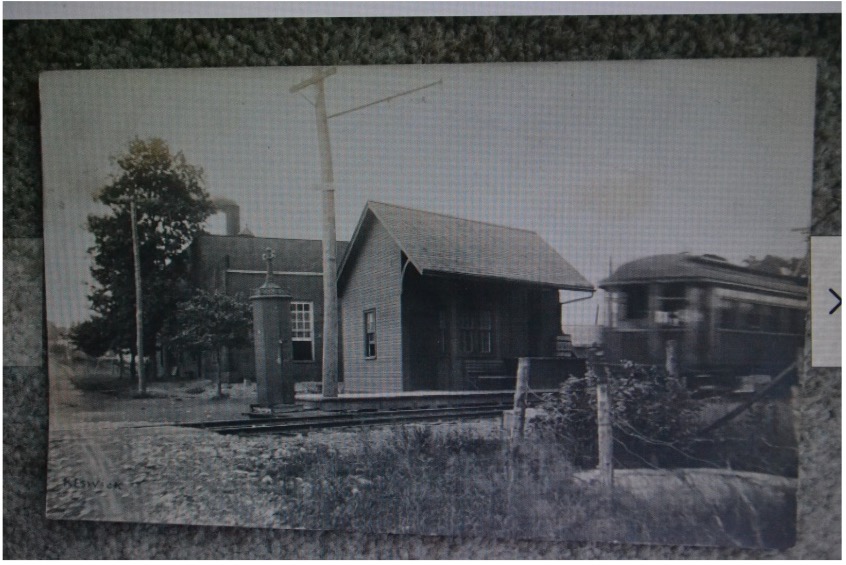

Where in Georgina?

Our previous mystery location was identified correctly by our President Paul Brady. Thanks Paul! It’s finally solved…it was the Orchard Beach General Store! We have a new mystery location on the right …where is it, and what is it?

Our Pioneer Ancestors

The crossroads community of Vachell was briefly mentioned by Paul Brady in his January article “Georgina, A Town of Many Towns.” Paul stated “To the north of Egypt, at the intersection of Park Road and Old Homestead Road, the hamlet of Vachelle appears on old maps. However, no trace of this town remains, and I would love to know more about it.” Your editor did a little digging and learned the following about this “ghost” hamlet from entrees in three early directories: Might’s for 1891-92, Polk’s for 1884-85, and best of all, Lovell’s Ontario Directory for 1871.

In the early 1890s Might’s Directory tells us that Vachell had a population of about 50 people and contained a Methodist Church, a public school, and a Post Office with Robert McClellan as Postmaster. McClellan also ran the general store while both Robert Stratton and John Yates were listed as a blacksmiths. In 1884 Polk’s listed the same individuals and had additionally listed George Turnbull as a carpenter. Polk’s described Vachell as “A small place in Georgina Township,” but gave no actual population figure. Lovell’s Ontario Directory of 1871 provided the most complete information. The hamlet was recorded with a population of 175 and had a listing of 30 names, most of whom were farmers. In the 1871 Lovell’s Ontario Directory Hugh Cooper was listed as Postmaster and McClellan’s name was nowhere to be found. James Baily was listed as a carpenter and carriage builder operating a company called James Baily and Sons. Additionally Mr. Cooper was also a storekeeper while both Stratton and Yates were recorded as blacksmiths. The population listed reflects those living on farms in the general vicinity. Still, with the Methodist Church, a school, a general store, a carriage builder, carpenters, and two blacksmith businesses, Vachell had much going for it in the beginning, but as industrialization progressed, it declined and ceased to function as a viable village; too many necessary functions were easily met by other nearby communities.

News

Help!! We still need additional directors. If you are interested in playing a role in the work we are doing, don’t hesitate to contact us. Sarah Harrison and Dee Lawrence have both resigned from our Board, Sarah to accept a full-time library position, and Dee to cut back on outside activities so she may provide more time for her busy personal life. Both will remain an active member of the GHS. Thank you for your excellent service Dee and Sarah.

The digitization strategy for the Archives has been approved by Georgina Town Council and may now be downloaded for viewing from the following website:

The Town of Georgina has accepted the recommendations of the document named “The Pioneer Cemeteries Management Plan”, an eighty page report prepared by LEES and Associates Consulting Ltd. Town Staff has recommended that council accept the report and implement the plan. This will mean that our long-neglected heritage cemeteries will start to get the attention they deserve, slowly bringing them up to a standard that we can be proud of. The Georgina Historical Society hopes to play a role in their rehabilitation, doing volunteer work on cutting back over-grown bushes and other tasks. If you are interested in helping out with this work, please contact a Board member.

The Georgina Heritage Advisory Committee was disbanded after the last municipal election, and for the first time since 1972 this volunteer group hasn’t played a role in the Town’s plans. An engaged group of concerned citizens met on April 4 to discuss these very problems, and a delegation was formed to bring attention to this situation. They will present the matter to council. On April 4th, several members of your Board were present in support.

We have also commenced initial planning for Harvestfest this upcoming September. We’re trying to bring in some new and interesting exhibits, demonstrations, and attractions to the event, and will need volunteers to help us out. So if you can help in any way, please contact any member of the board.

Events

Tuesday, April 16th – general meeting at the schoolhouse in Georgina Pioneer Village; 6:30 meet & greet, 7:00 PM meeting. Melissa Matt will give a presentation on Winter Sports in Georgina.

May 9th & 10th (Thursday & Friday) – Georgina Pioneer Village. Rise to Rebellion

Saturday, June 1st – Opening week-end of Georgina Pioneer Village

Saturday, September 21st – Harvestfest, Georgina Pioneer Village