Click to Download the PDF

Download the Word Doc

President’s Message

We’ve had a busy spring this year getting everything opened up and ready for summer. We have also had some interesting opportunities come our way to spread the word about Georgina’s rich history. During a visit to the local Rogers cable show “Georgina Life”, where I was sharing a set of photos from Georgina’s past with the show’s hosts Grant and Lynda, I was introduced to Charlotte Hale, the artistic director at the Georgina Centre for Arts and Culture. Charlotte was captivated by the images so we arranged to drop the photos off at the centre to be displayed, along with a couple of vintage cameras. The results were unveiled this past Thursday and the display turned out great! It’s on display for a limited time, so if you get a chance to see it, it’s well worth the visit.

Another opportunity presented itself in the form of a feature wall in the Keswick branch of Scotiabank. After sharing a few images with them, a postcard from Kim’s collection was chosen and blown up to fill the feature wall. The image is an interesting view of the Maskinonge River from the 1940’s, featuring Cameron’s boathouse in the foreground. It turned out beautifully, and if you are in the bank, take a moment to admire it.

Hoping for some movement on the Town of Georgina’s Cemetery Master Plan, I was disappointed on a recent visit to the Mann Cemetery in Keswick to find that nothing had been done. The cemetery is still overgrown, and another grave marker has been broken by a fallen tree limb. I have been assured that the Town has budgeted for the rehab but are still at the tendering stage. Hopefully things start to happen soon, as it is not looking any better just yet.

On a more encouraging note, headway was made in re-instating the Georgina Heritage Advisory Committee. Excellent presentations by Dee Lawrence and Allan Morton convinced the Town of Georgina Council to re-think the decision to disband the Committee, but as a consulting company has already been hired, re-instatement can not happen right away. However, we were assured that the Committee will be re-instated when the consultant’s contract expires. Dee has graciously supplied her speech for us to appreciate in this issue of our newsletter.

To wrap up, we have a fun event coming up for our general meeting on May 21. We are doing a photo exposition at the school house at the Georgina Pioneer Village. We will have lots of vintage photos from Georgina, and if you have some photos or postcards in your collection that you would like to share, please bring them along. I hope to see you there, as always we start at 6:30 with our formal meeting starting at 7pm.

See you on May 21, Paul Brady

Dee Lawrence’s Deputation to Council on May 8, 2024

Reinstatement of the Georgina Heritage Advisory Committee

Mayor Quirk, members of Council, staff and residents of Georgina:

Thank you for the opportunity to speak to you today. My name is Dee Lawrence, and although my family has not lived in this community for generations, as some who are seated here have, I put down roots in Georgina 38 years ago, raised my children here, and grew to love this area because of the people who built this community, the beauty of the land and the water, and the history behind all of it. That history is informed by lived experience, of stories told, and memories shared. There is a wealth of knowledge which exists among long-time residents which took decades to gather.

It is for this reason that the Ontario Heritage Act states that “creating and sustaining a municipal heritage committee… signals that your municipality is committed to celebrating the stories, places and events of the people that have shaped your community; that you are committed to harnessing local talent and expertise for conserving your heritage; that you are making a commitment to its citizens by making heritage conservation a priority.”

Yet, in spite of the fact that there has been an active Heritage Advisory Committee in Georgina for at least the last 52 years, offering input, advice and wisdom from the community and sharing its collective knowledge and expertise with Council, those voices were silenced after the last municipal election in 2022 when everything changed, and the long-standing Heritage Advisory Committee ceased to exist. It is curious that a new Environmental Advisory Committee, an Agricultural Advisory Committee, and an Accessibility Advisory Committee were all appointed after the new council was sworn in, but in a report dated Sept. 27, 2023, I quote: “the Heritage Advisory Committee has yet to be appointed for this term of Council largely due to resource constraints and the implications of Bill 23”. End of quote.

In a time of self-professed resource constraints, $100,000.00 was found in order to hire a heritage consultant from the city of Toronto to come to Georgina and identify which of our properties have historical value. These are facts which have already been documented. What is needed however, is the will, and the commitment from council to designate and maintain properties that have already been identified as being of historical significance. As far back as 2021, Council voted to direct the Town Clerk to proceed with the issuance of the notice of intent to designate Bonnie Park and Lorne Park, as well as the Jackson’s Point Marine Railway. Three years have passed and those properties are still awaiting designation. What makes all of this so critical is that when Bill 23 comes into effect on January 1, 2025, properties that have not received designation status will be erased from the Heritage Registers and those properties cannot be put back on the Register for another 5 years. That means they are not protected from being dug up, torn up, demolished or developed. They could simply disappear forever.

Bill 23 will bring significant changes to the designation process in Ontario, and there is a lot to worry about and much work to be done in just 8 short months.

That’s why this is such an urgent situation. Having someone work full-time on this project is absolutely necessary at this point if we are to preserve the historical assets that we have in this community. We welcome more help in this regard, and might I say that it is long overdue! It would be most advantageous to pool resources which already exist in Georgina. The Town could benefit greatly from drawing on the wealth of experience and expertise of residents who already possess an extensive, collective knowledge about significant landmarks and history of early residents, the growth of industries, the establishment of businesses, and other important historical events which have helped to shape the development of this community.

A functioning Heritage Advisory Committee would be able to support, and not hinder, the work of the newly hired Heritage Consulting team so that the process of evaluating the list of properties currently on the Heritage Register could be expedited. As you are well aware, this work needs to be done quickly and efficiently, and having more people working on this project, rather than fewer people who are not familiar with our community, makes the most sense so that we are able to achieve the best possible outcome before the January 1st, 2025 deadline.

It is absolutely critical that the prioritization of designation be informed by the voices of those who know our community best – those who have lived and worked and played here for years on end. 50 years from now, not too many of us sitting here will be able to raise our voices, but we raise them now so that those living in the Georgina of the future will be able to appreciate and learn from what we have been able to preserve from the past. The decisions we make today could have a profound and lasting impact on the ways in which future generations experience life in this Town.

In conclusion, I just want to emphasize that there is a need and a desire for community input into this process, and there are several qualified, enthusiastic residents in our Town whose passion, knowledge and expertise would serve us all well in this regard. Therefore, we respectfully request that this Council begin to advertise, interview and appoint prospective members who are willing to invest their time and energy into working with the new Heritage Consultant in a spirit of co-operation and collaboration in order to help identify the best way forward regarding Heritage concerns in Georgina. It doesn’t have to be one or the other – it really can be both!

Thank you for your time and consideration.

Dee Lawrence

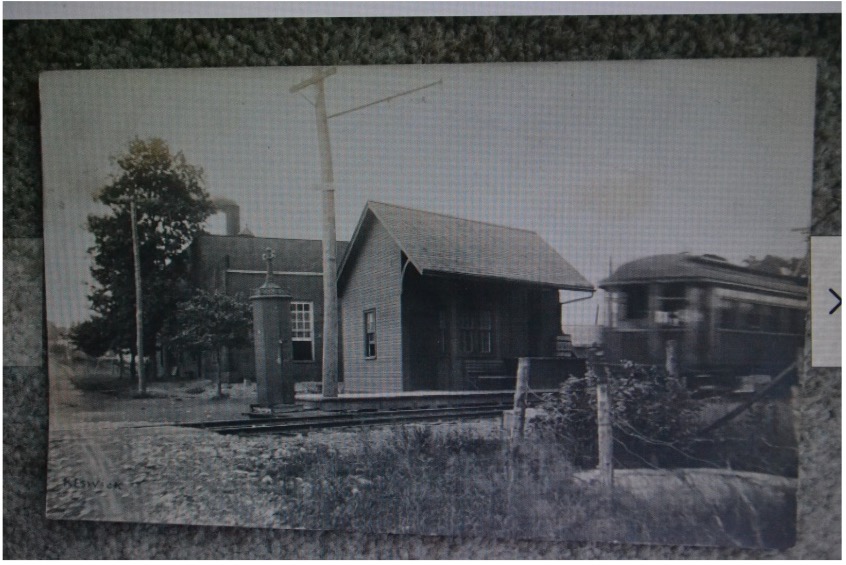

Where in Georgina?

Our previous mystery location was identified correctly by our President Paul Brady. Thanks Paul! It’s finally solved…it was the Orchard Beach General Store! We have a new mystery location on the right …where is it, and what is it?

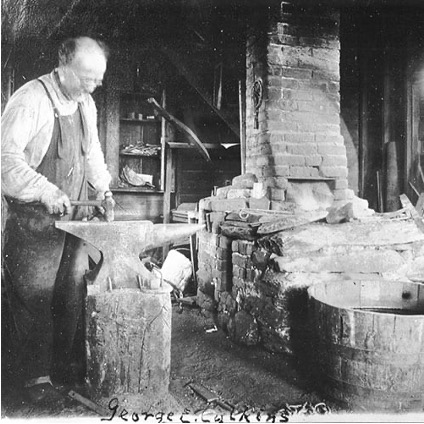

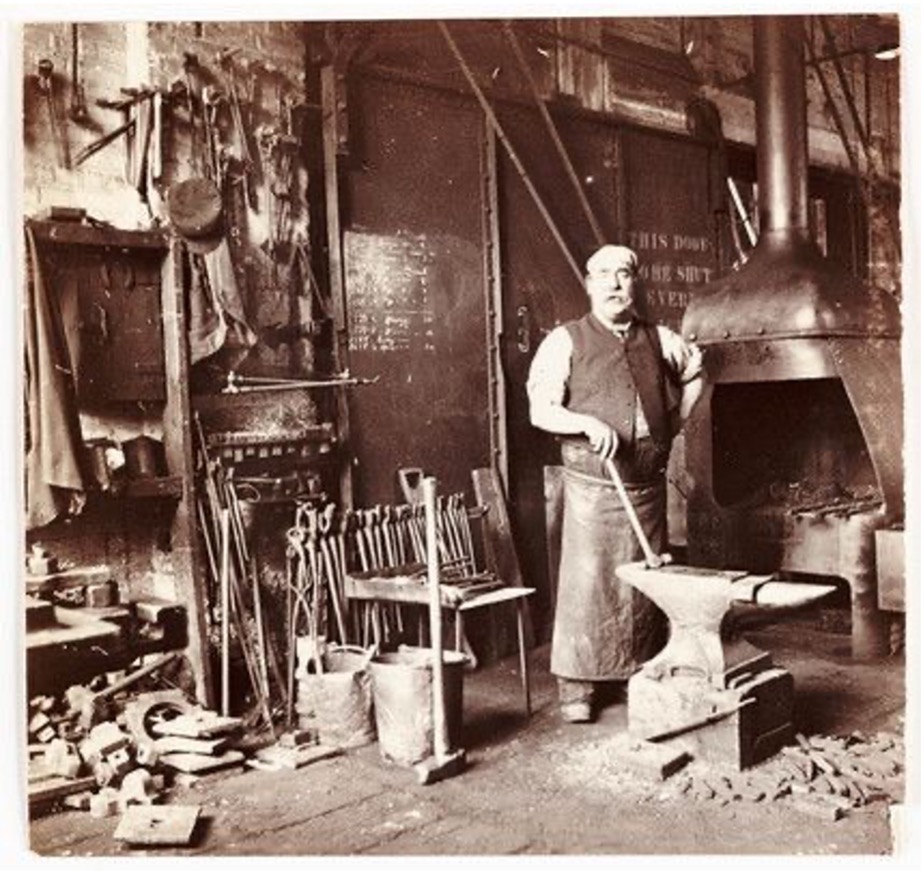

The Blacksmith

At Harvestfest 2024, this September, we hope to have a blacksmith present to demonstrate the skills of his trade in the blacksmith shop of Georgina Pioneer Village. We felt it appropriate to highlight the importance of early blacksmiths. The following is adapted from the internet resources listed at the end of the article. Ed

From the earliest days of settlement, a blacksmith was an extremely important part of every community. He was the proverbial jack-of-all-trades. While farmers took care of their tools, it was the blacksmith who was trained to make and repair these same tools. Using forge, anvil and hammer, the blacksmith worked with the single most important and common metal of the period; iron, and later with steel, producing hammers, axes, adzes, files, chisels, and carving tools. He made nails, screws, springs, bolts, chains, clamps, hinges, shutter fasteners, latches, fireplace cranes, pokers, spits, and other metal fittings used by settlers in construction, fitting, and maintenance of houses and other structures. The blacksmith also worked closely with the wagon-maker, wheelwrights, and the carpenter to supply the community’s needs and to create essential everyday products for use in the home and in the fields. Since the progress and prosperity of villages, towns, and surrounding townships were almost inseparable in the first half of the nineteenth century, smiths played a significant role in growth and prosperity. In backwoods settlements, far from places where tools and equipment could be bought, the blacksmith was the most important craftsman in town.

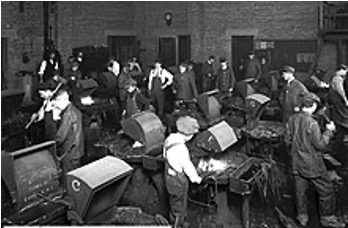

Even after the rise of industry in the second half of the 1800s, blacksmiths found ways to remain vital members of their communities by evolving their services to fit specific economic needs. In Georgina every village had at least one smith and larger communities supported two or more. In the latter part of the 1800s, the significance of blacksmiths shifted as industrialization mechanized the processes of many trades. Mass production threatened to replace the work of blacksmiths, as it allowed for faster and more cheaply made products that could be replaced instead of repaired. Before 1850, blacksmiths could forge nails at a rate of one per minute, making them relatively scarce and expensive. Nails proved so valuable that arsonists would burn down buildings just to collect the nails left behind. By the end of the century however, machines could make hundreds of nails per hour and at a cost that made nails easily replaceable instead of prized.

Blacksmiths responded to industrialization by turning attention to shoeing horses and making and repairing wagons and carriages. Factories had not yet replaced these products with a machine, and the increasing movement of people from farm to city required reliable means of transport. By shifting attention away from smaller projects and focusing instead on horses, transportation, and agricultural implements, smiths maintained their prestige as skilled tradesmen within the transportation industry despite the increasing prevalence of mass production in other sectors.

Blacksmiths had to be tradesmen and businessmen to manage successful workshops and provide a variety of services. Townspeople and farmers alike valued the range of skills blacksmiths possessed and relied on them to create the tools and implements necessary for survival. Smiths could manipulate metal in endless ways, but usually created and repaired farm equipment such as hoes, plows, rakes and other tools as well as made most kinds of simple hardware (nails, hinges, fasteners etc.), wheels for wagons, kitchen utensils and horseshoes. Blacksmiths who could take on an array of specialized projects had more value within their community than those who could not, so most smiths prioritized becoming a “jack of all trades” in order to strengthen their reputation and serve as many people as possible.

Smiths managed their businesses carefully and kept detailed records of daily work orders and the debts owed by their customers. They interacted with other business owners in their community to build solid professional networks and advertise their services. Working for themselves, smiths had to skillfully negotiate their compensation, which often took the form of cash payments, traded goods, or services promised by customers skilled in other trades. A successful blacksmith managed costs carefully to sustain himself and attract future patrons. Most charged for their services based on the type of project and the time it took to complete it. For the basic repair of farm implements such as plows, rakes, and other equipment, blacksmiths typically earned between one dollar and a dollar and a half per day. For the creation of a new product, blacksmiths could expect to earn an average of five and a half dollars per day.

Becoming a Blacksmith in the 1800s

The demand for blacksmiths in 19th century society led many young men to pursue the trade. Although there is evidence of female blacksmiths during this time period, males dominated. Becoming a smith required many years of careful study and dedication. In the early 1800s, master blacksmiths who worked in the trade most of their lives and had an ample set of skills took young apprentices into their homes and workshops. More often than not smithing ran in families with skills passed on from fathers to their offspring. Apprentices would be educated, fed, and clothed in exchange for assisting master blacksmiths in their shops and learning alongside them. Most apprentices during this time worked under a contract or learned from relatives skilled in the trade.

By around 1830, it was customary for master blacksmiths to pay apprentices a small wage for their help in the workshop instead of housing them. Most boys completed their apprenticeship and became journeyman blacksmiths by the age of twenty-one. As journeymen, they were considered competent in their trade and capable of performing a range of tasks related to both metalworking and bookkeeping, but did not have enough experience to be considered a master smith. It took many more years of work for young journeymen to gain complete mastery in the craft.

The Clothing and Tools

Smiths workwear was kept simple and utilitarian by dressing in everyday clothing covered by a leather apron for protection from stray sparks. Crafted from affordable cowhide, the apron allowed free movement while providing essential protection for the blacksmith from his waist to below the knees and was sometimes split in the middle to allow smiths to cradle the leg of a horse when fitting shoes. Sturdy boots were worn to protect their feet and a belt held their most frequently used tools. Smiths did not wear gloves because they preferred direct contact with the metal being worked.

A few essential pieces of large equipment and a number of small tools were used depending on the work being done. Every smith required a forge, bellows, and anvil to properly heat and shape their projects. Blacksmiths heated metal in forges fueled by a charcoal fire until it was hot enough to manipulate with small tools. Bellows helped concentrate air into the forge to make the fire hotter. By the end of the 19th century, most traditional bellows were replaced by rotary fan blowers, which performed more efficiently than traditional bellows. Once the metal heated up sufficiently, the smith would transfer it to his anvil for shaping. The anvil both absorbed the blows made by the blacksmith during shaping and provided multiple surfaces for working the metal. By 1900, many blacksmiths had added a drill press to their arsenal of large metalworking equipment.

Smaller tools varied depending on the job, but blacksmiths typically utilized hammers, tongs, forms, wedges, and chisels to complete their projects. Hammers and chisels helped form the metal into unique shapes. Tongs allowed blacksmiths to place pieces of metal closer to the hottest part of the coals for quicker and more thorough heating. If they did not possess the tools required for a specific job, blacksmiths would make their own. Over the span of a blacksmith’s career, he could accumulate hundreds of different tools that existed solely for the completion of one particular item. Blacksmiths often had trouble identifying the tools of other smiths because they were so individualized. This has made studying the process of 19th century blacksmithing difficult for modern historians as well because blacksmiths usually did not document each tool’s unique function.

Materials & Metals in the 19th century Smithy

Before the mid-1830s, blacksmiths worked with wrought iron; it was cheaper and more malleable than other metals on the market. By 1838, John Deere’s successful invention of the steel plow popularized that metal for craftsmen such as blacksmiths. Steel became more readily available for smiths and they began using steel for large farm implements, though they still relied heavily on wrought iron for smaller, everyday tools and repairs. Wrought iron and steel could be ordered from commercial manufacturers or bought directly from local general stores.

Merchants sold metal in hoops and bars of varying lengths and prices. In the 1830s, wrought iron cost six cents per pound on average, making it the most cost-effective choice for blacksmiths, while steel could cost between eighteen and twenty-five cents per pound. Buying new metal could be expensive regardless of which kind a blacksmith chose because of transportation fees from the general store to the workshop; so many smiths saved money by collecting scrap metal from previous projects and re-using it.

Inside the Workshop of an 1800s Blacksmith

Blacksmith shops of the 19th century were utilitarian in design allow smiths to maintain efficiency in their work and interactions with customers so they could complete more projects and optimize their daily wage. Small, one-room workshops were made of unfinished logs, lumber, brick, or stone depending on the climate and resources available. Most workshops had one or two windows, but less lighting was ideal; darkness allowed smiths to focus more easily on the glow of their heated metal. The most economical shops had dirt floors, but smiths preferred the comfort of wood and the warmth it sustained in the winter.

Blacksmiths designed their workshops with four distinct areas with specific purposes. The workspace contained the forge, central to the blacksmith’s craft, possessing a chimney and bellows on one side to concentrate the heat of the fire while an anvil stood handily by as it was used most often. Smiths who frequently made horseshoes and acted as a farrier would also keep a shoeing stand within their main workspace. Blacksmiths stored smaller and scarcely used tools around the perimeter of the forge and anvil, with the most necessary items kept close by.

The walls and corners of the workshop housed the blacksmith’s collection of recyclable scrap metal, coal fuel, and other refuse. Smiths maintained this stock of scrap for reworking into small tools or for repairs. Some smiths preferred to keep scrap and fuel outside of their workshops to save space and prevent accidental fires.

The final distinct area of the blacksmith’s workshop was the waiting area, usually with a fireplace to keep visitors warm in the colder months and a simple table and chairs. From this space, customers could watch the smith complete their order or relax with their pipes and newspapers.

People of all occupations and backgrounds relied on blacksmiths to create the items they needed for their everyday activities. The workshops of blacksmiths reflected the practicality of the smith and the items he created. Although small, these spaces allowed blacksmiths and their customers to engage in the art of metalworking with efficiency and ease. As demands shifted and new means of production emerged at the end of the 19th century, blacksmiths evolved their trade to maintain their status as skilled craftsmen and essential members of their communities.

Sources:

https://workingtheflame.com/medieval-blacksmith-daily-life/

https://19thcentury.us/19th-century-blacksmith/

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/blacksmithing

Our Pioneer Ancestors

Some Local Blacksmiths

Georgina Township

Baldwin – Nelson Draper, blacksmith (1890s)

John Prosser, blacksmith (1880s)

Virginia – John S. Atkinson, blacksmith (1890s)

Vachell – Robert Stratton, John Yates, blacksmiths (1870s through 1890s)…Yates also was a carpenter

James Baily, carpenter and carriage builder (1870s)

Pefferlaw – Joseph Foster, blacksmith (1890s)

John Griffith, blacksmith (1880s)

James Harrison, blacksmith (1870s)

Udora – Wm. J. Brown, blacksmith (1890s)

- Dafoe, and G Watson, blacksmiths (1880s)

Luke Doble, blacksmith (1870s)

- Cosgrove, Samuel McDowell, blacksmiths (1860s)

North Gwillimbury Township

Belhaven – Myron Silver, Joseph A. Sheppard, blacksmiths (1870s)

George Cowieson, blacksmith; Albert Dafoe, waggonmaker (1880s)

Jesse Connell, blacksmith; Albert Dafoe, waggonmaker (1890s)

Keswick (Roach’s Point, Roches Point, Medina) – Solomon Prosser, blacksmith (1870s)

Keswick (earlier Medina now Keswick) – Wm. Terry, blacksmith (1890s)

Peter Mellen, John & Samuel Trelan, blacksmiths (1860s)

Ravenshoe – Nelson Draper, blacksmith (1880s)

Graham Herbert, blacksmith (1890s)

Sources: from the following business directories – Anderson’s Ontario 1869, Lovell’s Ontario 1871, From Polk’s Ontario Directory 1884-5, and Might’s Directory 1891-92

News

Help!! We still need additional directors. If you are interested in playing a role in the work we are doing, don’t hesitate to contact us. Sarah Harrison and Dee Lawrence have both resigned from our Board, Sarah to accept a full-time library position, and Dee to cut back on outside activities so she may provide more time for her busy personal life. Both will remain an active member of the GHS. Thank you for your excellent service Dee and Sarah!

Volunteers are needed to help in the Georgina Pioneer Village on June 1st for the season’s opening celebration, please contact Melissa Matt at 905 476 4301 ext. 2284.

The Georgina Heritage Advisory Committee disbanded after the last municipal election, for the first time since 1972 will not played a role in the Town’s plans. An engaged group of concerned citizens met April 4 to discuss this problem, and a delegation was formed to bring this situation to council. That presentation was made on May 8th and its contents are reproduced elsewhere in this newsletter for your information.

Music in the Streets will come again to the Pioneer Village on Saturday June 22nd. Volunteers are needed for our GHS refreshment booth. Planning for Harvestfest has commenced for this upcoming September. We’re bringing in some new and interesting exhibits, demonstrations, and attractions to the event, and need volunteers to help us out. If you can help with either event, please contact any member of the board.

Events

May 9th & 10th (Thursday & Friday) – Georgina Pioneer Village. Rise to Rebellion

Tuesday, May 21st – general meeting at the schoolhouse in Georgina Pioneer Village; 6:30 meet & greet, 7:00 PM meeting. This will be an “Old Pictures Night” Do you have any old pictures of Georgina people, places and events that you can share? Bring ‘em along. We also have some early photos and tintypes, and could use help in identifying the people and places shown in them.

Saturday, June 1st – Opening week-end of Georgina Pioneer Village

Monday June 3rd – Board Meeting, 2:00 PM Georgina Pioneer Village Schoolhouse

Saturday, June 22nd – Music in the Streets, Georgina Pioneer Village

Saturday, September 21st – Harvestfest, Georgina Pioneer Village