Click to Download the PDF

Download the Word Doc

President’s Message

Welcome to our September newsletter. Just a brief note to update you on our September events; of course, Harvestfest is this Saturday, September 17 at the Pioneer Village. It is not too late to volunteer some time to welcome visitors, if you are available. Be sure to let your family, friends and neighbours know of this great event at the Pioneer Village. On Tuesday, September20 at 7: pm our General Meeting will be held at De La Salle Hall. Nancy Banks will be speaking on the history of Deer Park School. You won’t want to miss this interesting talk and slide show.

Looking forward to seeing you at these events!

Our Annual General Meeting will be coming once again this November. There are two openings coming up for two directors. If you are interested in a more active role in the Georgina Historical Society or know of someone who you know that would like to contribute by serving on the Board please contact me at btglover@rogers.com or our Vice-President, Paul Brady pkbrady@rogers.com.

Take care.

Tom Glover, President

Agricultural Implements: A Brief History

The following is an adaptation of an article written in 2013 by Alan Skeoch found online at https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/agricultural-implements . We felt it appropriate to run it in this our Harvestfest edition.

Canadian agriculture changed rapidly between 1850 and 1900, and changes in agricultural implements both caused and reflected changes in other sectors.

In addition to the spade, hoe and rake familiar to modern gardeners, early hand tools used in farming included the seeder, a perforated wooden trough carried by means of a strap around the neck and used in broadcast seeding; the sickle and the scythe, one- and 2-handed knives, respectively, used for cutting field crops and hay; the flail, 2 wooden rods attached by a strap and used to thresh out the kernels of grain; the winnowing tray, a 2-handled, half-moon-shaped receptacle used to cast flailed grain into the air so that the chaff could be blown away; the fork, used for pitching hay or shovelling manure; the wooden grain shovel; the hay knife and hay hook; and the grafting froe, a knife used to split branches in grafting. Most of these implements were superseded; others (eg, the plow) underwent substantial modification.

Some Implements

From wooden-moldboard, single-handled, home-made machines, plows became chilled-steel, mass-produced, scientifically designed 2-handled walking plows; then single-moldboard riding plows, double-moldboard riding plows, and finally giant machines with up to 16 moldboards. These alterations occurred as the source of power changed from oxen (best for root-strewn pioneer farms) to teams of horses, then to multiple teams of horses (up to 16 to a hitch), to steam-driven traction engines with the power of 50 or more horses, and finally to lighter, more versatile but equally powerful gasoline tractors.

Threshing machinery underwent the most dramatic and expensive changes. In 1850 most farmers cut their grain with cradle scythes, and the few short weeks of the harvest dictated the amount grown. In winter, cut grain was threshed on the barn floor, by beating with flails or treading with horses’ hooves until the kernel fell free of the straw and was scooped up and winnowed, by the wind or by an artificial wind created by a fanning mill.

More efficient machines (eg, the generation of reapers triggered by the inventions of Cyrus McCormick and Obed Hussey in the US and Patrick Bell in England) allowed farmers to harvest larger and larger amounts of grain. Larger threshing machines, initially powered by one- or 2-horse treadmills, and later by immense steam-driven traction engines, began to appear. Mechanical threshers were manufactured by Waterloo, Sawyer-Massey, Hergott, Lobsinger, Moody and other Canadian manufacturers.

Tillage machinery was also improved. Harrows made from tree branches, with iron spikes driven into them, were replaced by various steel-spring harrows that were able to tear freshly turned sod into a weed-free seedbed in much less time.

The Industry

Rapid change provided opportunities for industrialists. The tiny local blacksmiths’ shops of Canadian villages began to increase in size as the demand for iron increased, particularly after the railway boom of the 1850s, which allowed cheap iron to move more easily from England and the US. The demand for iron for engines, rolling stock and track led to the establishment of a sophisticated iron industry in Hamilton, Ontario.

Earlier ironmakers (eg, the Van Normans) had relied on poor-grade bog iron. In the 1850s higher-quality iron stimulated the growth of local foundries.

Iron began to replace wood in farm implements. Implement makers grew in number, particularly around the western end of Lake Ontario, where Massey, Verity, Patterson, Wilkinson, Sawyer, Cockshutt, Wisner, Harris and others established their factories, making plows, cutting boxes, fanning mills, seed drills, reapers, mowers, threshing machines and steam engines. Because it was cheap and plentiful, wood was used wherever possible. Iron, however, was essential for cutting and moving parts in general. Larger- and-larger-scale implement makers seemed to sprout up overnight; some of these companies, eg, those that were conservative or undercapitalized, disappeared as quickly; others thrived and continue to dominate the farm machinery industry into the late 20th century.

As one machine was rendered obsolete by the invention of an improvement (eg, the wire binder replacing the sail-reaper and itself replaced by the twine binder); the pace of competition accelerated. A few Canadian companies, eg, the plow maker William H. Verity, specialized in one implement; however, most of the big implement makers produced full lines of farm equipment. The Massey Manufacturing Company (originally established at Bond Head and later relocated at Newcastle, then Toronto, because of the need for a railway supply and delivery system) only made about 50-odd implements in 1847.

In 1860 it was making 2 classes of implements: simple machines of Canadian design (eg, straw cutters, harrows, wheelbarrows, fanning mills) and more complicated machines copied from American patents (eg, Manny’s Combined Reaper and Mower, Wood’s New Self-Raking Reaper, Pitt’s Horse Power, Ketchum’s Patent Mower). The manufacture of American machines in Canada was a matter of considerable pride and the absence of a patent law, until 1869, encouraged Canadian implement makers to make annual trips to the US in search of new ideas and special rights to manufacture new American inventions.

Ontario

Markets were strongest in western Ontario, where the rural majority in the 1850s had been able to set aside capital from the high grain prices caused by the Crimean War. In eastern Ontario the number of manufacturers was smaller but still significant, the most prominent being Frost and Wood of Smiths Falls, which survived the period of intense competition in the 1890s. Herring of Napanee, which marketed fanning mills and reapers, eventually folded, as Massey-Harris machines moved into a wider and wider market area after 1891. Not all implement makers stayed in that line of production; eg, the Gibbard Company of Napanee initially made fanning mills and coffins, then began making fine furniture, eventually dropping implement manufacturing completely.

Harvestfest 2019

Below is an image of a “September Harvest Day in the Village” in our 2022 issue of our calendar. On Saturday September 17th, we will continue this tradition which is rooted well into our past. Come and join with us to celebrate the harvest.

Harvest Festivals; An Historical Perspective

A harvest festival is an annual celebration that occurs around the time of the main harvest of a given region. Given the differences in climate and crops around the world, harvest festivals can be found at various times at different places. Harvest festivals typically feature feasting, both family and public, with foods that are drawn from crops.

In Britain, thanks have been given for successful harvests since pagan times. Harvest festivals are held in September or October depending on local tradition. The modern Harvest Festival celebrations include singing hymns, praying, and decorating churches with baskets of fruit and food in the festival known as Harvest Festival, Harvest Home, Harvest Thanksgiving or Harvest Festival of Thanksgiving.

In British and English-Caribbean churches, chapels and schools, and many Canadian churches, people bring in produce from the garden, the allotment or farm. The food is often distributed among the poor and senior citizens of the local community or used to raise funds for the church, or charity.

Nowadays the festival is held at the end of harvest, which varies in different parts of the world. Sometimes neighboring churches will set the Harvest Festival on different Sundays so that people can attend each other’s thanksgiving. Many harvest celebrations are not tied into religious observations and are held as fall fairs or events with food, music, exhibits and demonstration as their main focus.

Until the 20th century, most farmers celebrated the end of the harvest with a big meal called the harvest supper, to which all who had helped in the harvest were invited. It was sometimes known as a “Mell-supper”, after the last patch of corn or wheat standing in the fields which were known as the “Mell” or “Neck”. Cutting it signified the end of the work of harvest and the beginning of the feast. There seems to have been a feeling that it was bad luck to be the person to cut the last stand of corn. The farmer and his workers would race against the harvesters on other farms to be first to complete the harvest, shouting to announce they had finished. In some counties, the last stand of corn would be cut by the workers throwing their sickles at it until it was all down, in others the reapers would take it in turns to be blindfolded and sweep a scythe to and fro until all of the Mell was cut down.

Some churches and villages still have a Harvest Supper. The modern British tradition of celebrating the Harvest Festival in churches began in 1843, when the Reverend Robert Hawker invited parishioners to a special thanksgiving service at his church at Morwenstow in Cornwall. Victorian hymns such as Come, ye thankful people, come and All things bright and beautiful but also Dutch and German harvest hymns in translation (for example, We plough the fields and scatter) helped popularise his idea of a harvest festival, and spread the annual custom of decorating churches with home-grown produce for the Harvest Festival service. On 8 September 1854 the Reverend Dr William Beal, Rector of Brooke, Norfolk, held a Harvest Festival aimed at ending what he saw as disgraceful scenes at the end of harvest, and went on to promote ‘harvest homes’ in other Norfolk villages. Another early adopter of the custom as an organized part of the Church of England calendar was Rev Piers Claughton at Elton, Huntingdonshire in or about 1854.

As people have come to rely less heavily on home-grown produce in wealthier nations such as Britain, and Canada, there has been a shift in emphasis in many Harvest Festival celebrations. Increasingly, churches have linked the harvest with an awareness of and concern for people in the developing world for whom growing crops of sufficient quality and quantity remains a struggle. Development and Relief organizations often produce resources for use in churches at harvest time which promote their own concerns for those in need across the globe.

In the early days, there were ceremonies and rituals at the beginning as well as at the end of the harvest.

Encyclopædia Britannica traces the origins to “the animistic belief in the corn [grain] spirit or corn mother.” In some regions the farmers believed that a spirit resided in the last sheaf of grain to be harvested. To chase out the spirit, they beat the grain to the ground. Elsewhere they wove some blades of the cereal into a “corn dolly” that they kept safe for “luck” until seed-sowing the following year. Then they plowed the ears of grain back into the soil in hopes that this would bless the new crop.

Excerpted and adapted from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harvest_festival

Where in Georgina?

Elm Croft, Church Street, Keswick

There were a number of excellent guesses of the location for the image to the left. They identified homes of similar construction, but not in the right location. Both it and the new image presented in last month’s newsletter (below) were both correctly identified by Kim Brady.

Virginia United (formerly Methodist) church

Can you identify the location for the new image below?

Deer Park Public School By R. W. Holden

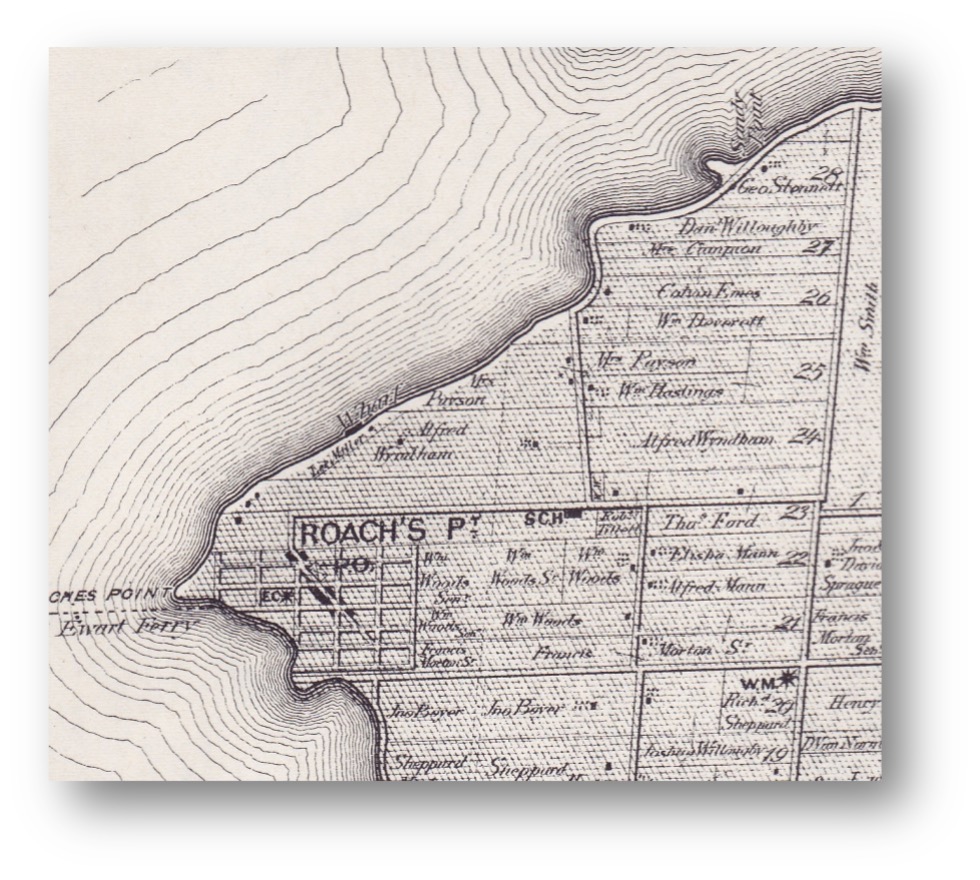

Deer Park Public School has one of the oldest school buildings still in use in all of York Region. This became my first school after graduating from Toronto Teacher’s College in 1973. In the Northeast end of Georgina near the shores of Lake Simcoe and Roches Point, it is situated on the southeast corner of Varney and Deer Park roads where there has been a school on the site since 1882…that’s 140 years! Prior to that, a school is shown on the south side of Deer Park Road just west of Varney Road in the York County Historical Atlas of 1878. (See the map at right).

In 1969 the small school boards of York County amalgamated to create the York County Board of Education. At this time many of the old one and two room schools were closed and sold. One of those schools was eventually moved into our Pioneer Village. Students were relocated to larger schools with more up to date facilities. Only a small number of these one-room schools remain within the fabric of our present day school buildings in York Region and Deer Park Public School is one of them.

The first school on the site of present day Deer Park Public School was built in 1882 and came to be known as Lakeview School, school section #6, North Gwillimbury. It was a frame building that was kept heated by a wood stove in the winter. In 1912, the school board built a new schoolhouse that cost a little over $4000. That 120 year old brick structure remains part of Deer Park Public School today.

In the next 10 years many improvements were made including the acquisition of a piano, flagpole and a school garden. In 1930, an addition to the school for junior classes was constructed. By 1953 the school expanded yet again with a third classroom being added in the basement. A second addition was added to the school in 1954, which sustained a growing population until 1969 when a new wing was added to Deer Park projecting east from the south side of the old building..

The school continued to grow in the 1970’s and 1980’s. The school received a gymnasium and a library in 1972 and several portable classrooms by 1985. I arrived there shortly after the gym and library were added. At that time Deer Park served students from kindergarten to grade seven. George Easy was the Principal. Today under the leadership of Principal Catherine Robinson Buyukozer, the school continues to serve the community north and east of Keswick from kindergarten through grade eight having an enrolment of 190 students.

Our Pioneer Ancestors

EDWARD Ross, lot 12, concession 5, was born in North Gwillimbury Township in the year 1839. He was married in 1858; he had no issue.*

*Excerpted from: History of Toronto and County of York, Volume II; C. Blackett Robinson, Publisher 1885, p. 503.

News

The GHS will need all hands on deck to help with Harvestfest. If you can help or would like more information, please contact Kim or Paul Brady at (905) 853-8005 or any GHS Board member for further information. Members will also be advised of any other event information in future issues of the GHS newsletter.

The school house in the Pioneer Village still is not open as yet. Approvals for its use have not been forthcoming from the Buildings Department of the Town. Though a heritage reconstruction, the building was deemed a “new build” and as such must meet the more stringent building code requirements of today. We suspect that none of today’s vintage buildings in the Village would pass the current building code test. Yet, after well over 100 years they are all still standing and in use!

Our Annual Meeting is coming up inNovember. There are openings on the Board for two Directors. If you are interested in a more active role in the Georgina Historical Society or know of someone you know that would like to contribute by serving on the Board please contact Tom Glover at btglover@rogers.com or Paul Brady at pkbrady@rogers.com

Events

June 21st – General meeting with a tour of the renovated Caboose, and new Village signage.

June 25th – Music in the Streets. The GHS will be running a refreshment booth for this event.

July 1st – Canada Day at the Pioneer Village…volunteers needed. Parking will at the Lawn Bowling Green…volunteers meet at the Bandshell at 1:30

August 5th, 6th, and 7th – Sutton Fair 1st weekend in August volunteers need for our booth.

September 17th – Harvest Day at Georgina Pioneer Village…help needed here too!